Macrophages play a pivotal role in inflammation and tissue homeostasis. However, their effects on inflammation are complex and contradicting, orchestrating both the initiation and resolution of inflammatory responses. Read on to learn more about the complex role of macrophages in inflammation and their potential therapeutic applications.

Understanding macrophages and inflammation

Macrophages are critical players in the body’s immune responses as they regulate the initiation and resolution of inflammation.1 Elucidating the complex role of macrophages in inflammation requires a better understanding of the functions of macrophages and the cellular and molecular pathways involved in the different steps of inflammation.What are macrophages?

Macrophages are large, specialized immune cells that form a critical part of our innate immune system.2 Key characteristics include:- Derived from monocytes in the blood2

- Found in virtually all tissues of the body3

- Highly phagocytic, capable of engulfing pathogens and cellular debris2

- Long-lived cells with the ability to self-renew in tissues4

- Express a wide range of pattern recognition receptors (PRRs)5

Overview of inflammation

Inflammation is the body’s natural defense against harmful stimuli such as pathogens, damaged cells, or toxic compounds.8 The inflammatory process involves several steps9:- Release of pro-inflammatory mediators and signaling molecules

- Increased blood flow to affected areas, causing redness and heat

- Enhanced vascular permeability, leading to swelling

- Recruitment and activation of immune cells

- Pain sensation to promote protective behavior

What role do macrophages play in inflammation?

Macrophages are crucial players in both acute and chronic inflammation, performing various functions throughout the inflammatory process:- Pathogen recognition and engulfment: Macrophages express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs) that detect pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), enabling them to phagocytose invading microorganisms and cellular debris.11

- Release of pro-inflammatory cytokines and mediators: These include TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, chemokines reactive oxygen species (ROS), and nitric oxide (NO).12

- Recruitment and activation of other immune cells: Macrophages bridge innate and adaptive immunity by interacting with other immune cells, including T cells, B cells, and neutrophils.13

- Tissue repair and resolution of inflammation: At late stages of the inflammatory process, macrophages switch to anti-inflammatory phenotypes that promote healing. They also produce growth factors and matrix-remodeling enzymes and clear apoptotic cells through efferocytosis.14

Macrophage polarization: a spectrum of activation

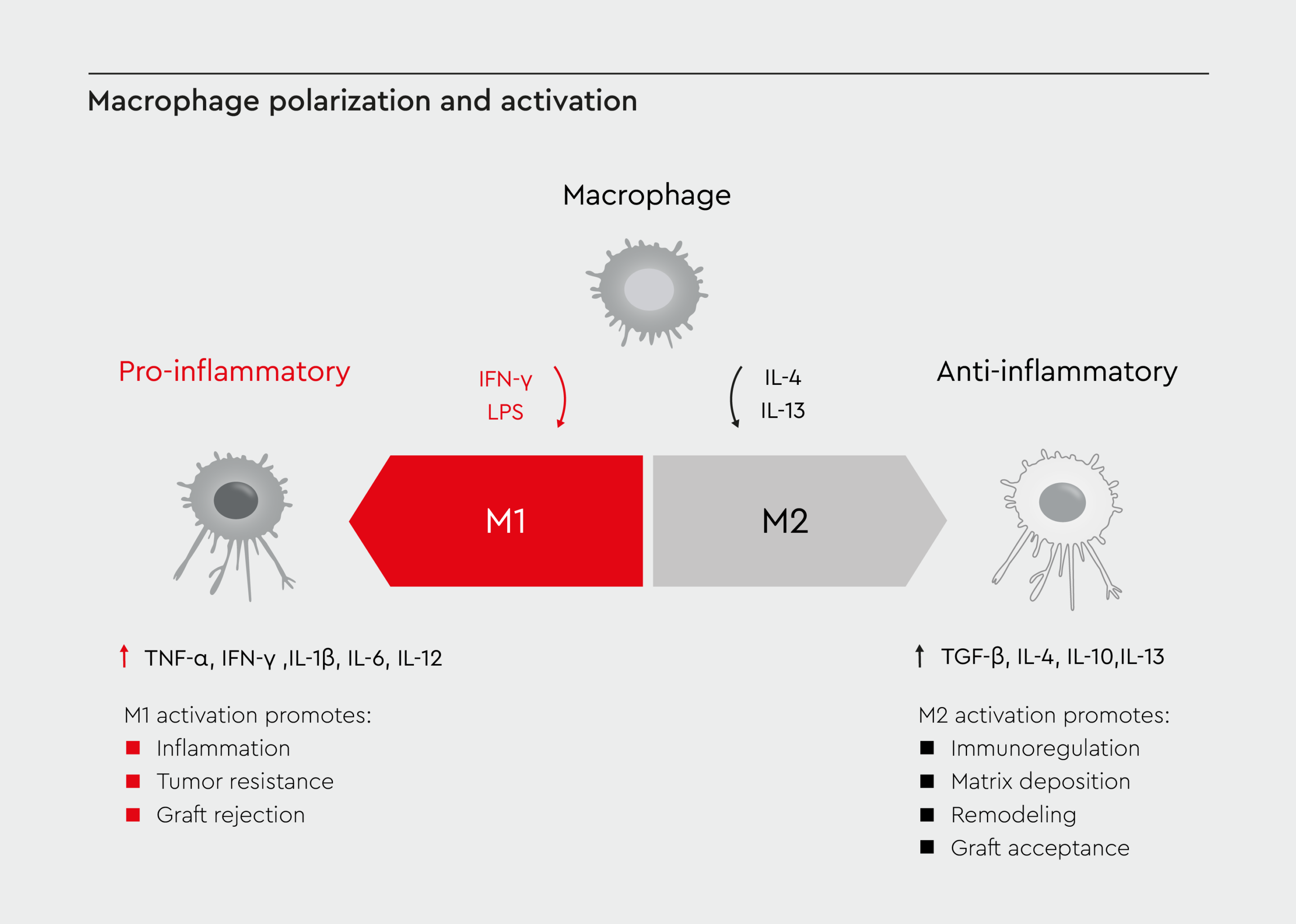

Despite being specialized cells, macrophages have remarkable plasticity and can adopt different functional states in response to environmental cues (Figure 1).15,16 This adaptability allows them to respond effectively to various challenges, from infection to tissue injury. The polarization state of macrophages can be reversed or altered as conditions change. Factors influencing macrophage plasticity include cytokines, growth factors, microbial products, metabolic signals, and physical cues (e.g., tissue stiffness).17 Although macrophage plasticity is more than black and white, it is often simplified into two main categories: M1 macrophages (classically activated) and M2 macrophages (alternatively activated).15,16 Macrophages in vivo often exhibit mixed or intermediate phenotypes.

Figure 1: Macrophage polarization and activation.

A visual representation of macrophage polarization, showing the continuum from M1 (pro-inflammatory) to M2 (anti-inflammatory) phenotypes. Adapted from Lee 2019.16

M1 macrophages

M1 macrophages exert pro-inflammatory effects by producing high levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-12), ROS, and NO. They also express high levels of MHC-II for antigen presentation and promote Th1 immune responses.16 M1 activation is induced by interferon-γ (IFN-γ) and lipopolysaccharide (LPS) and is regulated by the transcription factors NF-κB, STAT1, and IRF5.18M2 macrophages

M2 macrophages have anti-inflammatory effects and can be further subdivided into M2a, M2b, M2c, and M2d subtypes.16 They produce anti-inflammatory cytokines (IL-10, TGF-β), supporting Th2 immune responses. M2 macrophages also express high levels of scavenger receptors, promoting tissue repair and angiogenesis.16 M2 activation is induced by IL-4, IL-13, IL-10, and glucocorticoids and is regulated by the transcription factors STAT6, PPARγ, and KLF4.18Role of macrophages in immune regulation

M1 and M2 macrophages play distinct roles in the inflammatory process, working in concert to maintain tissue homeostasis.3,15Coordination of immune response

M1 macrophages initiate and sustain inflammation by producing pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines and presenting antigens to T cells to activate the adaptive immune system. They also activate B cells and neutrophils.19 In contrast, M2 macrophages resolve inflammation and promote tissue repair by producing anti-inflammatory cytokines and growth factors.19Transition from acute to chronic Inflammation

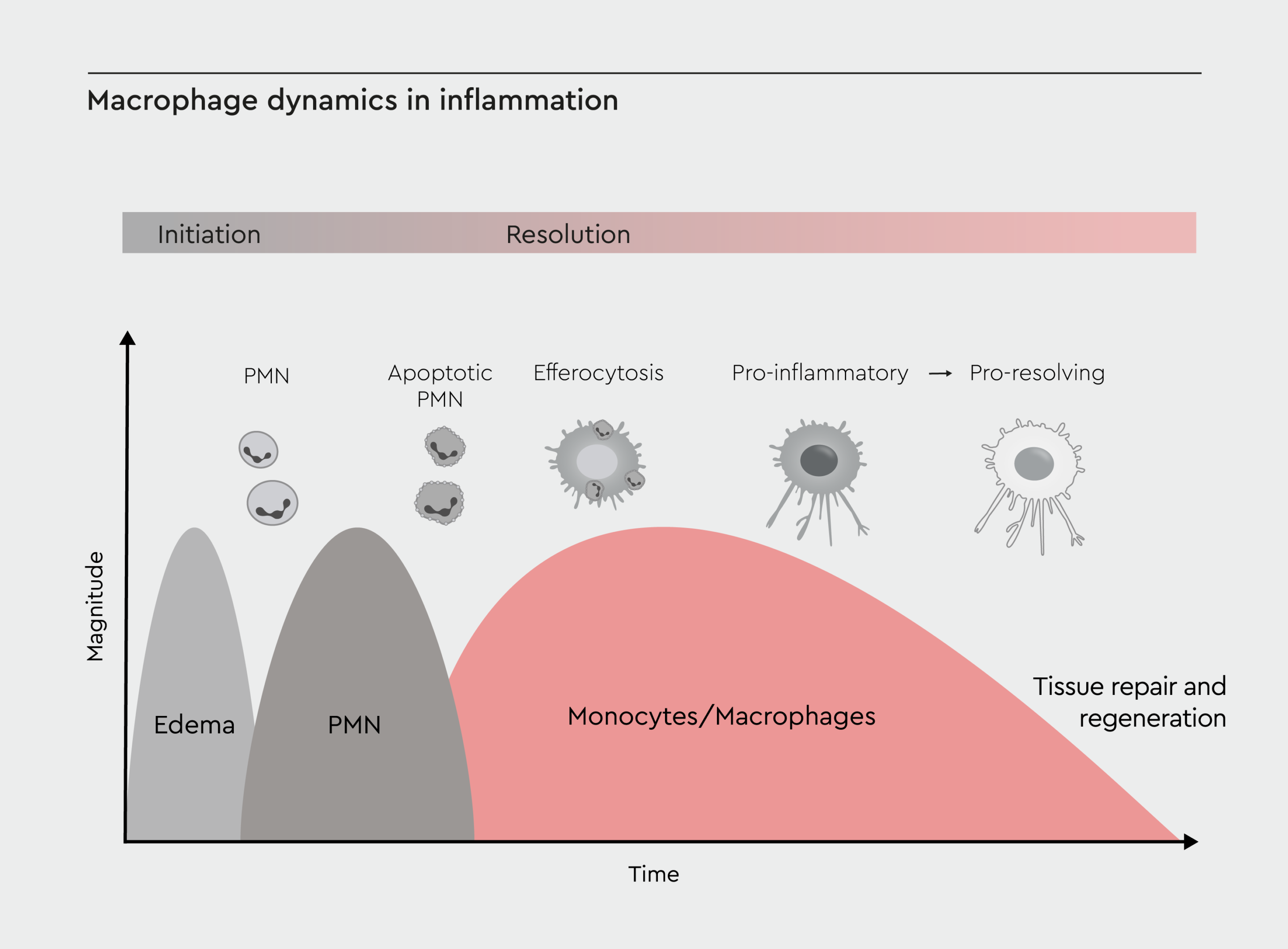

Macrophages are pivotal in determining whether inflammation resolves or becomes chronic (Figure 2).20 Although polymorphonuclear leukocytes (PMNs) are the main drivers of the acute phase of inflammation, M1 macrophages also play a role in the recruitment of neutrophils and other immune cells and the clearance of pathogens or tissue debris.20 During the resolution phase, macrophages shift toward the M2 phenotype and produce pro-resolving mediators (e.g., resolvins, protectins).20 Persistent imbalance between M1 and M2 phenotypes can lead to chronic inflammation, with continued production of pro-inflammatory mediators. This can lead to tissue damage and fibrosis.21

Figure 2: Macrophage dynamics in inflammation.

Timeline of inflammation, highlighting the roles of macrophages at different stages: initiation, progression, resolution, and potential chronic inflammation. Adapted from Sansbury et al., 2016.20

Role of macrophages in disease

The balance between M1 and M2 phenotypes is crucial for maintaining tissue homeostasis and proper immune function. Dysregulation of this balance is associated with various pathological conditions, including chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer.22Inflammatory diseases

Macrophages contribute to various inflammatory conditions:- Atherosclerosis: Production of pro-inflammatory mediators and matrix-degrading enzymes contributes to foam cell formation in arterial walls and plaque instability.23

- Osteoarthritis: Production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and tissue-degrading enzymes exacerbates infiltration of synovial tissue and activation of synovial fibroblasts.24

- Inflammatory bowel disease: Excessive pro-inflammatory cytokine production can lead to dysregulated responses to gut microbiota and impaired intestinal barrier function.25

Obesity and insulin resistance

Macrophages play a crucial role in obesity-related inflammation and metabolic dysfunction.26 Accumulation in adipose tissue during obesity results in a shift from anti-inflammatory M2 to pro-inflammatory M1 phenotype and formation of crown-like structures around adipocytes.27 In turn, dysfunctional adiposity contributes to chronic low-grade inflammation, characterized by the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines (TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-6) and activation of inflammatory signaling pathways (e.g., NF-κB, JNK).27,28 Metabolic dysfunction and obesity-related inflammation can contribute to insulin resistance as they interfere with insulin signaling in adipose tissue.29Wound repair and tissue regeneration

Macrophages are essential for proper wound healing.30 During the initial inflammatory phase of wound healing, M1 macrophages promote clearance of pathogens and debris and recruitment of additional immune cells.14,30 At the proliferative phase, M2 macrophages promote angiogenesis, fibroblast proliferation, and extracellular matrix deposition.14,30 During the remodeling phase, the balance between M1 and M2 functions is critical for matrix remodeling, scar formation, and tissue function restoration.14,30 Macrophages also contribute to tissue regeneration by producing growth factors (e.g., VEGF, PDGF, TGF-β), regulating stem cell function, and modulating the extracellular matrix.31Macrophage-targeting approaches

The ability of macrophages to shift between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory states makes them attractive targets for modulating immune responses in various pathological conditions.Inflammatory conditions

Chronic inflammatory conditions are characterized by persistent M1 activation. Therefore, modulating macrophage activation and polarization has emerged as a promising approach for the treatment of inflammatory diseases.32 Modulating macrophage polarization, inhibiting pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, and enhancing resolution of inflammation have shown promising results in preclinical studies of using macrophage-targeted therapies for chronic inflammatory conditions.33Promotion of tissue regeneration

Macrophage-based therapies for tissue regeneration focus on harnessing the pro-regenerative properties of M2 macrophages.34 Promising strategies include:- Cell-based therapies: Adoptive transfer of ex vivo-polarized M2 macrophages to promote tissue repair in various conditions, such as renal injury.34

- Biomaterial-based approaches: Development of scaffolds and hydrogels that modulate macrophage behavior to enhance tissue regeneration. These materials can incorporate bioactive molecules that promote M2 polarization or recruit endogenous macrophages to the site of injury.35

- Growth factor delivery: Controlled release of growth factors that promote M2 polarization and tissue repair, such as IL-4, IL-10, or TGF-β.36

Research trends and future directions

The field of macrophage biology is evolving rapidly, with several new avenues of research. Researchers are increasingly using primary cells for more translatable results as primary monocyte-derived macrophages better reflect in vivo conditions.37 The THP-1 cell line remains useful for initial screening and mechanistic studies.40 Moreover, single-cell RNA sequencing and proteomics are increasingly being used to better understand macrophage heterogeneity and identify novel therapeutic targets.39 Integrating multi-omics data is also being used to develop comprehensive models of macrophage function in health and disease.42 Another promising research avenue is the application of Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) technology to produce CAR macrophages for cancer immunotherapy.40 This approach combines the phagocytic ability of macrophages with targeted recognition and has the potential for the treatment of solid tumors and hematologic malignancies.43 In addition, macrophage-based cell therapies harnessing the immunomodulatory capacity of macrophages are being developed for the treatment of inflammatory and degenerative diseases.41How we empower macrophage research

We offer a range of high-quality products to support macrophage and inflammation research:- Human M1 Macrophages (GM-CSF) are monocyte-derived, polarized, non-activated, primary human M1 macrophages from a single donor.

- Human M2 Macrophages (M-CSF) are monocyte-derived, polarized, non-activated, primary human M2 macrophages from a single donor.

- M1-Macrophage Generation Medium XF is a serum-free and xeno-free medium optimized for the generation of M1 macrophages from fresh monocytes.

- M2-Macrophage Generation Medium XF is a serum-free and xeno-free medium optimized for the generation of M2 macrophages from fresh monocytes.

- Macrophage Base Medium XF is a customizable serum-free and xeno-free medium for the generation of macrophages from fresh monocytes.

References

Expand

- Oishi Y, Manabe I. Macrophages in inflammation, repair and regeneration. Int Immunol. 2018;30(11):511-528.

- Varol C, Mildner A, Jung S. Macrophages: development and tissue specialization. Annu Rev Immunol. 2015;33(1):643-675.

- Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. The phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;19(1):92.

- Röszer T. Understanding the biology of self-renewing macrophages. Cells. 2018;7(8):103.

- Taylor PR, Martinez-Pomares L, Stacey M, Lin H-H, Brown GD, Gordon S. Macrophage receptors and immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2005;23(1):901-944.

- Italiani P, Boraschi D. From monocytes to M1/M2 macrophages: phenotypical vs. functional differentiation. Front Immunol. 2014;5:514.

- Davies LC, Jenkins SJ, Allen JE, Taylor PR. Tissue-resident macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2013;14(10):986-995.

- Abdulkhaleq LA, Assi MA, Abdullah R, Zamri-Saad M, Taufiq-Yap YH, Hezmee MNM. The crucial roles of inflammatory mediators in inflammation: A review. Vet world. 2018;11(5):627.

- Ji J, Yuan M, Ji R-R. Inflammation and pain. In: Neuroimmune Interactions in Pain: Mechanisms and Therapeutics. Springer; 2023:17-41.

- Ward PA. Acute and chronic inflammation. Fundam Inflamm. 2010;3:1-16.

- Sato S, St‐Pierre C, Bhaumik P, Nieminen J. Galectins in innate immunity: dual functions of host soluble β‐galactoside‐binding lectins as damage‐associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) and as receptors for pathogen‐associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). Immunol Rev. 2009;230(1):172-187.

- Ranneh Y, Ali F, Akim AM, Hamid HA, Khazaai H, Fadel A. Crosstalk between reactive oxygen species and pro-inflammatory markers in developing various chronic diseases: a review. Appl Biol Chem. 2017;60:327-338.

- Černý J, Stříž I. Adaptive innate immunity or innate adaptive immunity? Clin Sci. 2019;133(14):1549-1565.

- Kim SY, Nair MG. Macrophages in wound healing: activation and plasticity. Immunol Cell Biol. 2019;97(3):258-267.

- Rasheed A, Rayner KJ. Macrophage responses to environmental stimuli during homeostasis and disease. Endocr Rev. 2021;42(4):407-435.

- Lee KY. M1 and M2 polarization of macrophages: a mini-review. Med Biol Sci Eng. 2019;2(1):1-5.

- Xue J-D, Gao J, Feng C, Wu D-L. Shaping the immune landscape: Multidimensional environmental stimuli refine macrophage polarization and foster revolutionary approaches in tissue regeneration. Heliyon. 2024.

- Wang N, Liang H, Zen K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage M1–M2 polarization balance. Front Immunol. 2014;5:614.

- Lee C-H, Choi EY. Macrophages and inflammation. J Rheum Dis. 2018;25(1):11-18.

- Sansbury BE, Spite M. Resolution of acute inflammation and the role of resolvins in immunity, thrombosis, and vascular biology. Circ Res. 2016;119(1):113-130.

- Smigiel KS, Parks WC. Macrophages, wound healing, and fibrosis: recent insights. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2018;20:1-8.

- Shapouri‐Moghaddam A, Mohammadian S, Vazini H, et al. Macrophage plasticity, polarization, and function in health and disease. J Cell Physiol. 2018;233(9):6425-6440.

- Newby AC. Metalloproteinase expression in monocytes and macrophages and its relationship to atherosclerotic plaque instability. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28(12):2108-2114.

- Zhang H, Cai D, Bai X. Macrophages regulate the progression of osteoarthritis. Osteoarthr Cartil. 2020;28(5):555-561.

- Meng EX, Verne GN, Zhou Q. Macrophages and gut barrier function: guardians of gastrointestinal health in post-inflammatory and post-infection responses. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(17):9422.

- Xu L, Yan X, Zhao Y, et al. Macrophage polarization mediated by mitochondrial dysfunction induces adipose tissue inflammation in obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(16):9252.

- Revelo XS, Luck H, Winer S, Winer DA. Morphological and inflammatory changes in visceral adipose tissue during obesity. Endocr Pathol. 2014;25:93-101.

- Varra F-N, Varras M, Varra V-K, Theodosis-Nobelos P. Molecular and pathophysiological relationship between obesity and chronic inflammation in the manifestation of metabolic dysfunctions and their inflammation‑mediating treatment options. Mol Med Rep. 2024;29(6):95.

- Makki K, Froguel P, Wolowczuk I. Adipose tissue in obesity‐related inflammation and insulin resistance: cells, cytokines, and chemokines. Int Sch Res Not. 2013;2013(1):139239.

- Koh TJ, DiPietro LA. Inflammation and wound healing: the role of the macrophage. Expert Rev Mol Med. 2011;13:e23.

- Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44(3):450-462. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015

- Parisi L, Gini E, Baci D, et al. Macrophage polarization in chronic inflammatory diseases: killers or builders? J Immunol Res. 2018;2018(1):8917804.

- Li M, Wang M, Wen Y, Zhang H, Zhao G, Gao Q. Signaling pathways in macrophages: molecular mechanisms and therapeutic targets. MedComm. 2023;4(5):e349.

- Spiller KL, Koh TJ. Macrophage-based therapeutic strategies in regenerative medicine. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2017;122:74-83.

- Alvarez MM, Liu JC, Trujillo-de Santiago G, et al. Delivery strategies to control inflammatory response: Modulating M1–M2 polarization in tissue engineering applications. J Control Release. 2016;240:349-363.

- Yang H-C, Park HC, Quan H, Kim Y. Immunomodulation of biomaterials by controlling macrophage polarization. Biomim Med Mater From Nanotechnol to 3D Bioprinting. 2018:197-206.

- Lee CZW, Kozaki T, Ginhoux F. Studying tissue macrophages in vitro: are iPSC-derived cells the answer? Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(11):716-725.

- Bakker OB, Aguirre-Gamboa R, Sanna S, et al. Integration of multi-omics data and deep phenotyping enables prediction of cytokine responses. Nat Immunol. 2018;19(7):776-786.

- Cochain C, Vafadarnejad E, Arampatzi P, et al. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the transcriptional landscape and heterogeneity of aortic macrophages in murine atherosclerosis. Circ Res. 2018;122(12):1661-1674.

- Klichinsky M, Ruella M, Shestova O, et al. Human chimeric antigen receptor macrophages for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Biotechnol. 2020;38(8):947-953.

- Chan MWY, Viswanathan S. Recent progress on developing exogenous monocyte/macrophage-based therapies for inflammatory and degenerative diseases. Cytotherapy. 2019;21(4):393-415.

Contact our experts Contact our specialists to help you find the right products for your studies and stay at the forefront of macrophage research.