Imagine a world where we can study human organs without invasive procedures or animal testing. Thanks to organ-on-a-chip (OOC) technology, this is now a reality. These miniature organs are transforming drug development and biomedical research, offering new insights into human physiology in a controlled environment — read on to learn how.

What is an organ-on-a-chip?

Organ-on-a-chip models are 3D microfluidic devices that mimic the functions and responses of an entire organ or organ system in vitro.1,2 Often no larger than a USB drive, these microfluidic devices contain living human cells arranged to simulate the structure and function of human organs.3 By recreating the microenvironment of specific organs, these systems offer a more accurate representation of human physiology than traditional 2D cell cultures.1,2How does organ-on-a-chip work?

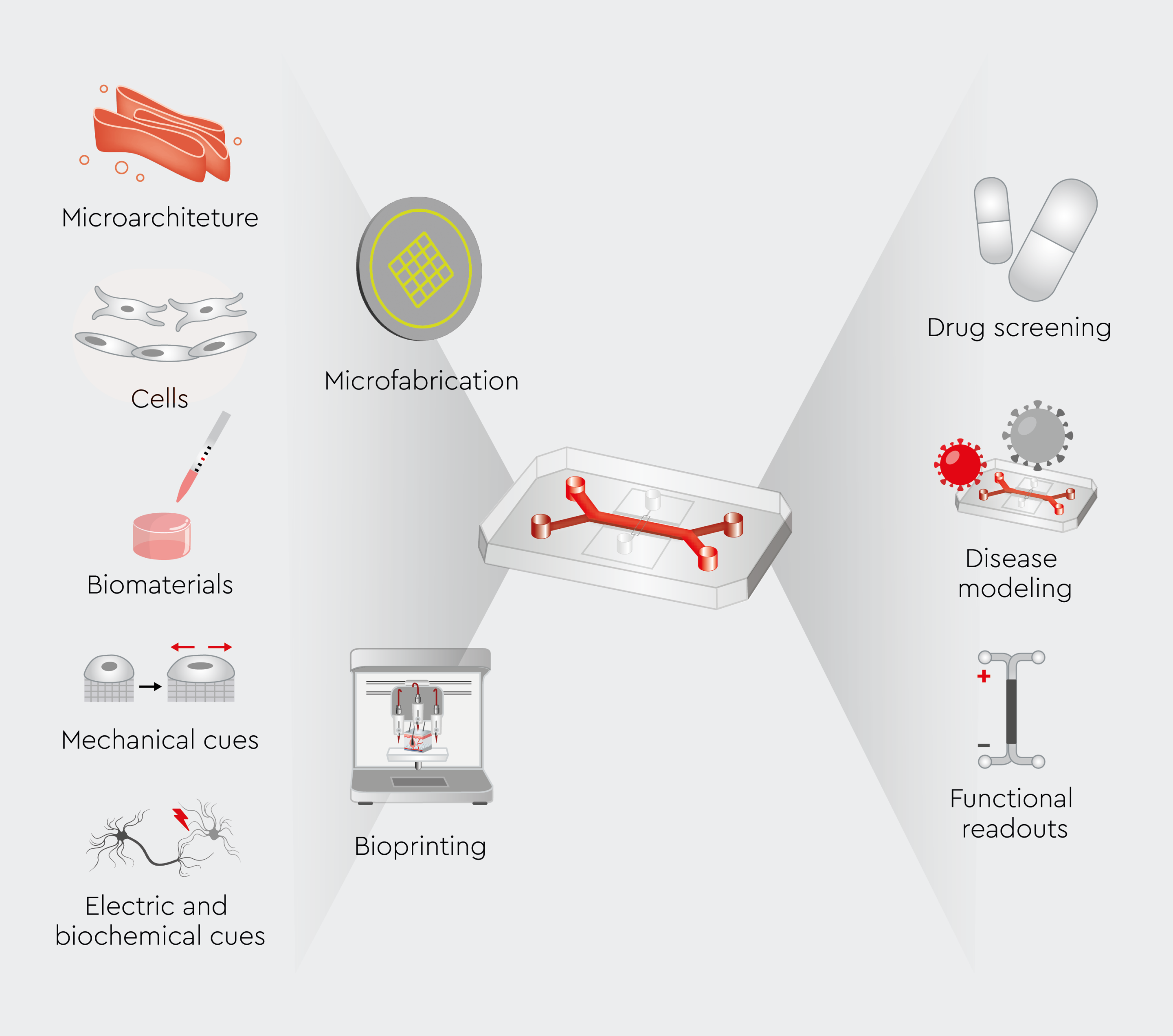

Organ-on-a-chip systems integrate various cell types and extracellular matrices arranged in 3D structures to recreate the microenvironment of human organs (Figure 1).4 They also incorporate microfluidic channels that mimic blood flow, thereby providing continuous nutrient supply and waste removal. In addition, these systems can integrate mechanical forces to simulate organ function.4 Common sources of cells used in organ-on-a-chip systems include endothelial cells, epithelial cells, fibroblasts, human cardiac myocytes, and immune cells.2,5 These cells are carefully cultured within the microfluidic channels of the chip, allowing the study of their interactions and responses to various stimuli, including potential drug compounds.2,6 The design of the systems varies depending on the organ being modeled. For instance, lung-on-a-chip systems typically incorporate stretching motions to simulate breathing, while liver-on-a-chip devices focus on replicating the complex metabolic functions of hepatocytes.7,8

Figure 1: Schematic illustration of organ-on-a-chip systems.

Components, structure, and design of organ-on-a-chip technology. From Cho S et al., 2023.4

Applications of organ-on-a-chip technology

Organ-on-a-chip technologies have a wide range of applications in drug development and biomedical research.- Drug discovery: These devices enable rapid screening of drug candidates, potentially reducing the time and cost of bringing new medications to market.9

- Disease modeling: Researchers can recreate disease conditions on chips, offering new insights into disease mechanisms and potential treatments.10 For example, cancer-on-a-chip models have been developed for the study of tumor growth and metastasis.11

- Toxicity testing: Organ-on-a-chip models provide a more accurate platform for assessing the toxicity of new compounds compared to traditional 2D cell cultures.12 This is particularly valuable for industries like cosmetics and environmental health, where animal testing is increasingly restricted.13

- Personalized medicine: By incorporating a patient’s own cells, these systems can help predict individual responses to treatment.14 This could lead to more tailored therapeutic approaches, reducing the risk of adverse reactions and improving treatment outcomes.

- Immunology research: These systems allow for detailed study of immune responses in a controlled environment.15 This is particularly valuable for understanding autoimmune diseases, allergies, and the body’s response to pathogens.

- Blood-brain barrier studies: Specialized chips modeling the blood-brain barrier can help us understand how drugs penetrate this crucial protective layer, potentially leading to more effective treatments for neurological disorders.16

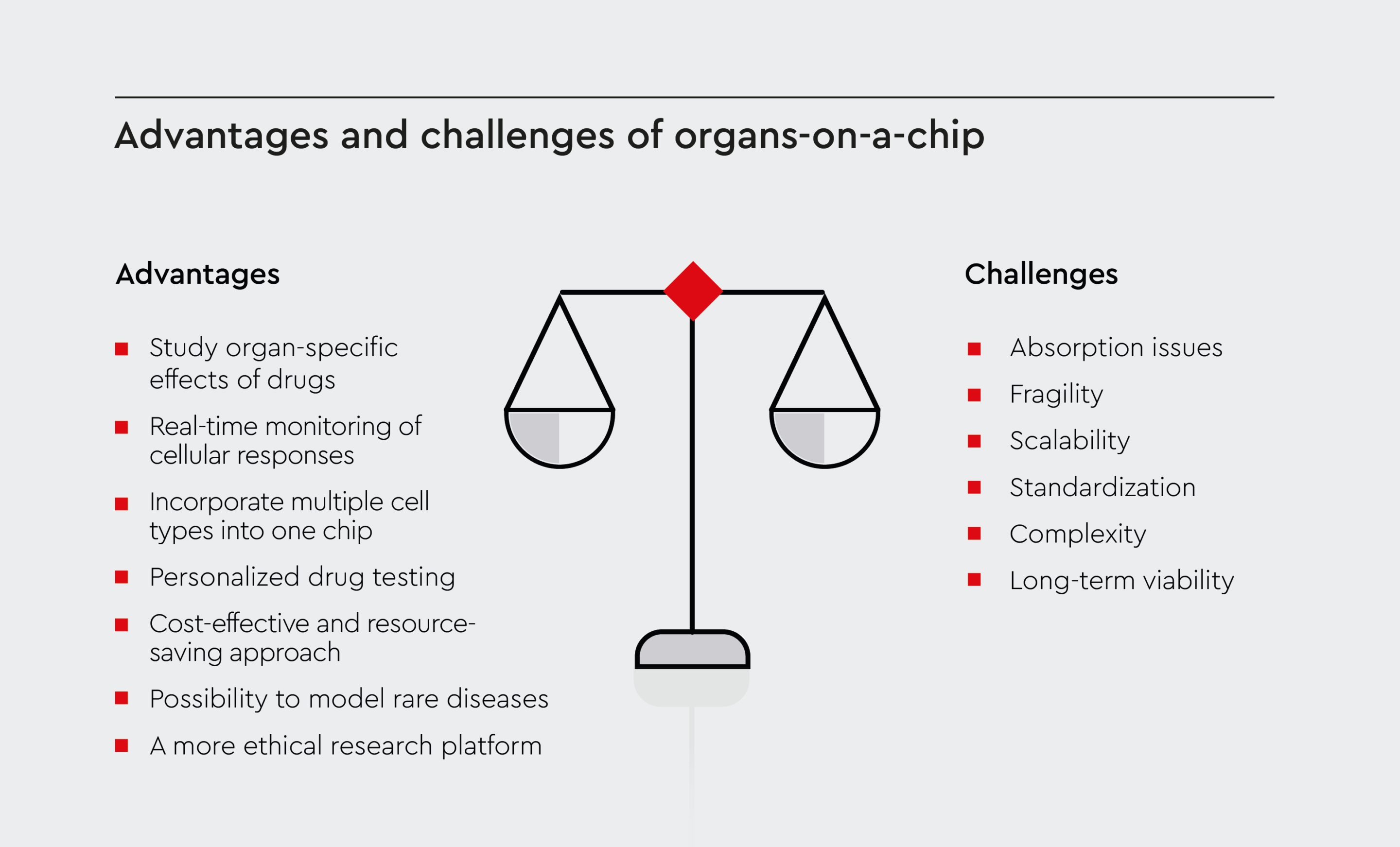

Advantages of OOC technologies

Organ-on-a-chip technology offers several advantages over traditional research methods (Figure 2):- Physiological relevance, providing a more accurate representation of human physiology than 2D cell cultures or animal models.17

- Ability to study organ-specific effects of drugs, helping to predict organ toxicity early in the drug development process.18

- Real-time monitoring of cellular responses, allowing for dynamic studies of drug effects over time.19

- Opportunity to incorporate multiple cell types into a single chip, enabling the study of complex cell-cell interactions.6

- Potential for personalized drug testing using patient-derived cells.19

- Reduced cost and time in drug development processes by enabling more efficient screening of drug candidates.19

- A more ethical research platform that doesn‘trely on animal testing, addressing concerns related to the use of animal models.20

- Possibility to model rare diseases or patient-specific conditions that may be difficult to study in animal models.21

Figure 2: Advantages and challenges of organs-on-a-chip.

Schematic illustration of the key benefits of OOC over traditional research methods, as well as their limitations.

Challenges and limited accuracy of organ-on-a-chip

Despite their several advantages over traditional research models, organ-on-a-chip systems face barriers to their widespread use (Figure 2):- Absorption issues: Some chip materials can absorb small molecules, potentially affecting experimental results.22

- Fragility: The delicate nature of these devices can make them challenging to work with, requiring specialized handling and expertise.23

- Scalability: Scaling up production of these systems for high-throughput screening can be difficult.24

- Standardization: There’s a lack of universally accepted protocols and materials for developing these models, making it challenging to compare results across different labs and experiments.25

- Complexity: Recreating the full complexity of human organs remains a significant challenge. Although these systems are more physiologically relevant than 2D cultures, they can’t fully replicate the complexity of human organs.24,26

- Long-term viability: Maintaining cells in a functional state on a chip for extended periods can be challenging, limiting the ability to study long-term effects or chronic conditions.5

Current trends and future prospects in OOC research

This field is evolving rapidly. Researchers are working on connecting multiple organ chips to create ‘body-on-a-chip’ systems, which could provide insights into complex inter-organ interactions and systemic effects of drugs.27 Standardization efforts are also a key focus, aiming to develop universally accepted protocols and materials. Ensuring consistent and reproducible results across different laboratories and experiments is crucial for the successful translation of findings from organ-on-chipmodels.26 Moreover, efforts are ongoing to develop new materials that minimize the risk of inaccurate findings due to chip materials absorbing small molecules. For example, the use of glass-based devices has been proposed to minimize small molecule absorption by materials used in organ-on-a-chip models.22 In addition, the integration of more sophisticated sensors into organ-on-a-chip devices could allow for even more detailed real-time monitoring of cellular responses.28 As the technology matures and guardrails for standardization are developed, increased adoption in the pharmaceutical and biotechnology industries is expected.29References

Expand

- Yan J, Li Z, Guo J, Liu S, Guo J. Organ-on-a-chip: A new tool for in vitro research. Biosens Bioelectron. 2022;216:114626.

- Yesil‐Celiktas O, Hassan S, Miri AK, et al. Mimicking human pathophysiology in organ‐on‐chip devices. Adv Biosyst. 2018;2(10):1800109.

- Ahadian S, Civitarese R, Bannerman D, et al. Organ‐on‐a‐chip platforms: a convergence of advanced materials, cells, and microscale technologies. Adv Healthc Mater. 2018;7(2):1700506.

- Cho S, Lee S, Ahn SI. Design and engineering of organ-on-a-chip. Biomed Eng Lett. 2023;13(2):97-109.

- Leung CM, De Haan P, Ronaldson-Bouchard K, et al. A guide to the organ-on-a-chip. Nat Rev Methods Prim. 2022;2(1):33.

- Rothbauer M, Zirath H, Ertl P. Recent advances in microfluidic technologies for cell-to-cell interaction studies. Lab Chip. 2018;18(2):249-270.

- Huh D. A human breathing lung-on-a-chip. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2015;12(Supplement 1):S42-S44.

- Kanabekova P, Kadyrova A, Kulsharova G. Microfluidic organ-on-a-chip devices for liver disease modeling in vitro. Micromachines. 2022;13(3):428.

- Ma C, Peng Y, Li H, Chen W. Organ-on-a-chip: a new paradigm for drug development. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2021;42(2):119-133.

- Ingber DE. Human organs-on-chips for disease modelling, drug development and personalized medicine. Nat Rev Genet. 2022;23(8):467-491.

- Imparato G, Urciuolo F, Netti PA. Organ on chip technology to model cancer growth and metastasis. Bioengineering. 2022;9(1):28.

- Messelmani T, Morisseau L, Sakai Y, et al. Liver organ-on-chip models for toxicity studies and risk assessment. Lab Chip. 2022;22(13):2423-2450.

- Pistollato F, Madia F, Corvi R, et al. Current EU regulatory requirements for the assessment of chemicals and cosmetic products: challenges and opportunities for introducing new approach methodologies. Arch Toxicol. 2021;95:1867-1897.

- Caballero D, Kaushik S, Correlo VM, Oliveira JM, Reis RL, Kundu SC. Organ-on-chip models of cancer metastasis for future personalized medicine: From chip to the patient. Biomaterials. 2017;149:98-115.

- Polini A, Del Mercato LL, Barra A, Zhang YS, Calabi F, Gigli G. Towards the development of human immune-system-on-a-chip platforms. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(2):517-525.

- Kawakita S, Mandal K, Mou L, et al. Organ‐on‐a‐chip models of the blood–brain barrier: recent advances and future prospects. Small. 2022;18(39):2201401.

- Pun S, Haney LC, Barrile R. Modelling human physiology on-chip: historical perspectives and future directions. Micromachines. 2021;12(10):1250.

- Lacombe J, Soldevila M, Zenhausern F. From organ-on-chip to body-on-chip: The next generation of microfluidics platforms for in vitro drug efficacy and toxicity testing. Prog Mol Biol Transl Sci. 2022;187(1):41-91.

- Jodat YA, Kang MG, Kiaee K, et al. Human-derived organ-on-a-chip for personalized drug development. Curr Pharm Des. 2018;24(45):5471-5486.

- Ingber DE. Is it time for reviewer 3 to request human organ chip experiments instead of animal validation studies? Adv Sci. 2020;7(22):2002030.

- de Mello CPP, Rumsey J, Slaughter V, Hickman JJ. A human-on-a-chip approach to tackling rare diseases. Drug Discov Today. 2019;24(11):2139-2151.

- Hirama H, Satoh T, Sugiura S, et al. Glass-based organ-on-a-chip device for restricting small molecular absorption. J Biosci Bioeng. 2019;127(5):641-646.

- Zarrintaj P, Saeb MR, Stadler FJ, et al. Human organs‐on‐chips: a review of the state‐of‐the‐art, current prospects, and future challenges. Adv Biol. 2022;6(1):2000526.

- Probst C, Schneider S, Loskill P. High-throughput organ-on-a-chip systems: Current status and remaining challenges. Curr Opin Biomed Eng. 2018;6:33-41.

- Tajeddin A, Mustafaoglu N. Design and fabrication of organ-on-chips: promises and challenges. Micromachines. 2021;12(12):1443.

- Candarlioglu PL, Dal Negro G, Hughes D, et al. Organ-on-a-chip: Current gaps and future directions. Biochem Soc Trans. 2022;50(2):665-673.

- Picollet-D’hahan N, Zuchowska A, Lemeunier I, Le Gac S. Multiorgan-on-a-chip: a systemic approach to model and decipher inter-organ communication. Trends Biotechnol. 2021;39(8):788-810.

- Fuchs S, Johansson S, Tjell AØ, Werr G, Mayr T, Tenje M. In-line analysis of organ-on-chip systems with sensors: Integration, fabrication, challenges, and potential. ACS Biomater Sci Eng. 2021;7(7):2926-2948.

- Homan KA. Industry adoption of organoids and organs‐on‐chip technology: toward a paradox of choice. Adv Biol. 2023;7(6):2200334.

Contact our experts As cell culture experts, we provide high-quality primary human cells and specialized media to ensure reproducible results. Contact our specialists to discover how our products can accelerate your OOC model research.