The traditional view of macrophages as ‘good’ or ‘bad’ immune cells has become outdated. Recent studies have shown that macrophage plasticity encompasses a complex spectrum of activation states, each of which plays an important role in health and disease. In this article, we discuss the latest understanding of macrophage polarization, the challenges in standardizing nomenclature, and why standardization is important for the development of new therapeutic approaches.

What is macrophage plasticity and why does it matter?

Macrophage plasticity refers to the remarkable ability of these innate immune cells to adapt their phenotype and function in response to environmental signals, including cytokines, pathogens, cellular debris, and metabolic signals.1,2 Unlike other immune cells with fixed phenotypes and functions, macrophages can alter their gene expression, surface markers, and functional outputs based on the molecular cues they encounter.1

This flexibility enables macrophage populations to serve various functions:

- Pathogen elimination: Detecting and destroying invading microorganisms through phagocytosis and secretion of antimicrobial substances.

- Tissue repair: Promoting healing and regeneration after injury by clearing debris and releasing growth factors.

- Homeostasis maintenance: Regulating normal physiological processes to maintain internal balance.

- Metabolic regulation: Controlling tissue metabolism and energy balance through interactions with other metabolic tissues, such as adipose tissue, liver, and muscle.

The plasticity of macrophages becomes particularly important during disease states. In cancer, for example, tumor progression often involves the reprogramming of macrophages from anti-tumor to pro-tumor phenotypes.3 Understanding these transitions opens new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The evolution from M1/M2 to spectrum-based classification

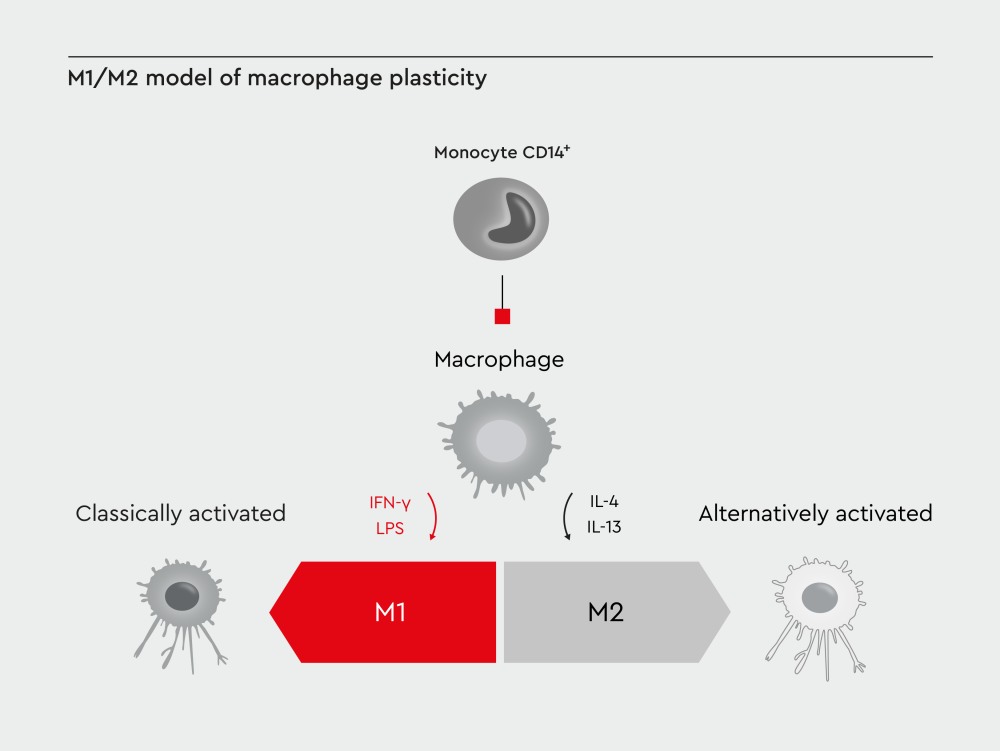

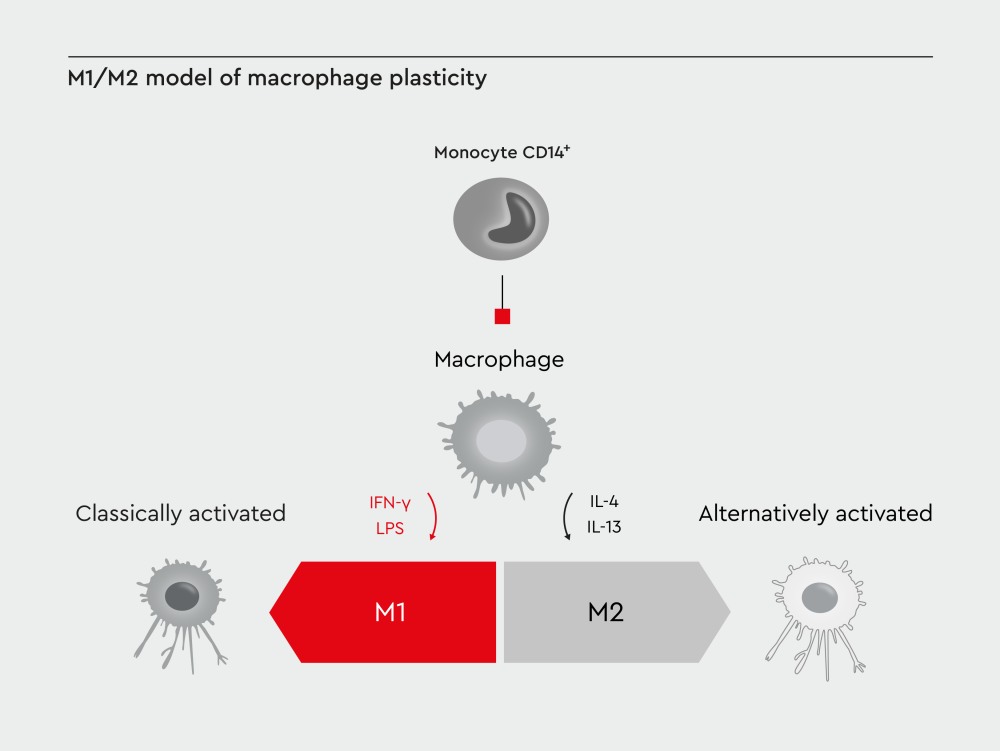

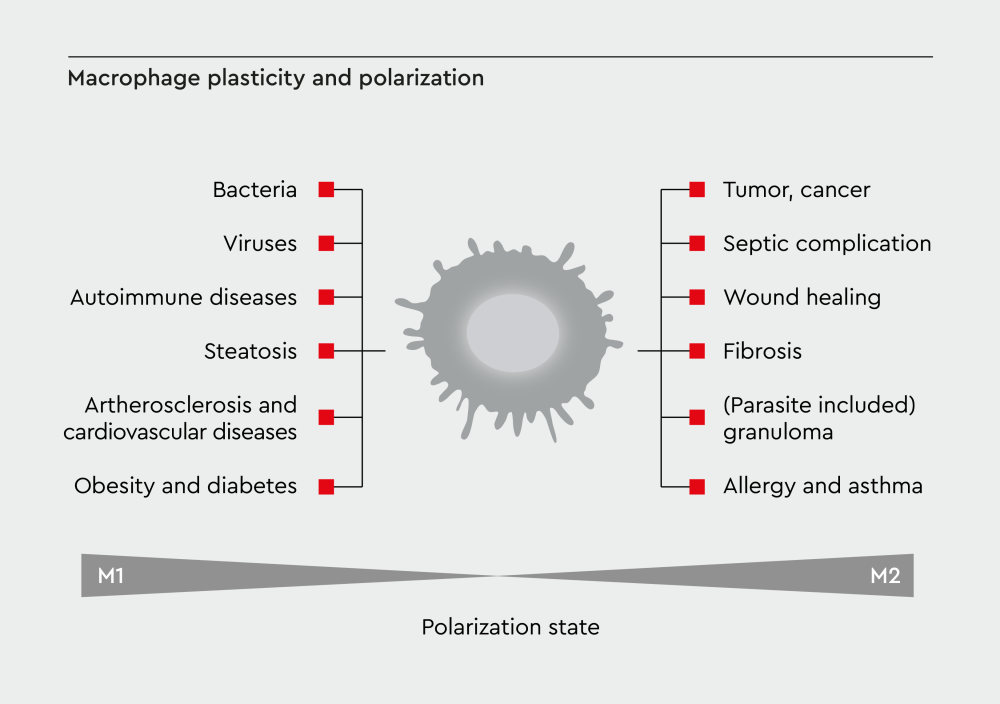

For decades, researchers classified macrophages into two categories: M1 (classically activated) and M2 (alternatively activated) macrophages.4,5 This binary system provided a useful framework but oversimplified the true nature of macrophage plasticity.

Traditional M1/M2 model

The M1/M2 classification emerged in the 1990s when researchers observed distinct responses to different stimuli.4,5

M1 macrophages are polarized in vitro by Th1 cytokines such as colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α), and interferon-γ (IFN-γ) alone or together with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) from bacteria. M1 macrophages express pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-12, IL-23, and TNF-α.6 M1 macrophages play a crucial role in pathogen killing by exhibiting strong cytotoxic activity and mediating resistance against infections.7,8

In contrast, M2 macrophages are polarized by Th2 cytokines such as IL-4 and IL-13 and produce anti-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-10 and transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β). M2 macrophages play a crucial role in tissue repair, particularly in the later stages of wound healing.9

Figure 1: M1/M2 model of macrophage plasticity. Traditionally, macrophages have been classified as M1 (classically activated) and M2 (alternatively activated) macrophages.

Spectrum of macrophage polarization

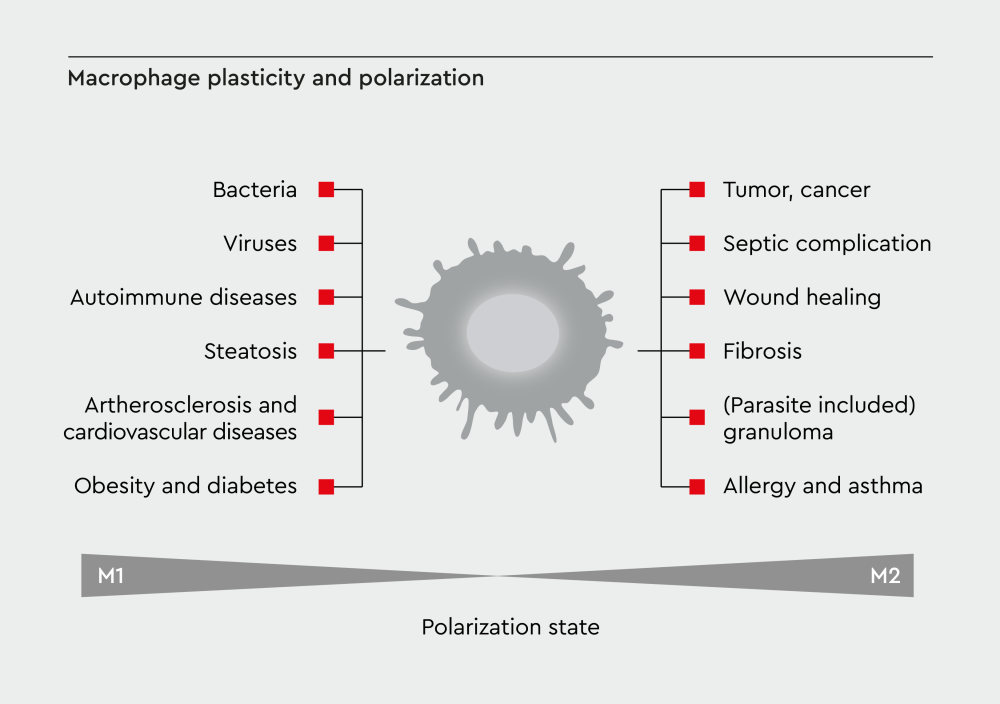

More recent studies have shown that macrophage plasticity extends far beyond the traditional binary classification into M1 and M2 phenotypes.10 Polarized macrophages exist along a continuous spectrum, with most cells displaying mixed characteristics.

Dr. Hagen Wieland from our development department explains: “The limitations of the M1/M2 model for defining macrophage polarization are becoming increasingly clear. These terms identify extremes of a continuum that rarely occur in living organisms.”

Several factors contribute to this complexity in macrophage phenotypes11–14:

- Local microenvironment: Tissue-specific signals influence macrophage polarization

- Temporal dynamics: Macrophage phenotypes can change over time

- Mixed signals: Macrophages often receive multiple, sometimes conflicting cues

- Intermediate states: Macrophages can exhibit characteristics that are between classical M1 and M2 phenotypes

Figure 2: Macrophage plasticity spectrum. Macrophage polarization exists along a continuous spectrum, rather than along discrete M1/M2 categories. Environmental signals drive transitions between different activation states, with most macrophages displaying mixed phenotypic characteristics. The traditional binary M1/M2 model oversimplifies this complex biological process.

Molecular mechanisms driving macrophage plasticity

The molecular basis of macrophage plasticity involves complex networks of transcription factors, signaling pathways, and epigenetic modifications that control gene expression.15

Key signaling pathways

Different stimuli activate distinct molecular cascades that promote macrophage polarization.

M1 polarization pathways16:

- NF-κB activation promotes inflammatory gene expression

- STAT1 signaling drives classical activation programs

- IRF family transcription factors regulate interferon responses

- HIF-1α supports glycolytic metabolism

M2 polarization pathways16:

- STAT6 activation follows IL-4/IL-13 stimulation

- PPAR-γ promotes alternative activation

- KLF4 regulates M2-specific gene programs

- STAT3 supports anti-inflammatory responses

Metabolic reprogramming

Macrophage plasticity doesn’t just involve changes in the genes they express or the signals they respond to. It also entails shifts in their metabolism, which is linked to their function.17–20

M1 metabolism relies heavily on glycolysis for rapid energy production, which helps them respond quickly to infection and produce large amounts of inflammatory molecules. However, glycolysis is less efficient, so it supports short bursts of activity, ideal for rapid immune responses.

M2 metabolism uses oxidative phosphorylation and fatty acid oxidation, which are slower but more efficient energy sources. This metabolic setup supports sustained activity needed for tissue repair, anti-inflammatory functions, and long-term homeostasis. However, macrophages can exist in metabolic states that fall between the extremes of the classical M1 and M2 phenotypes.

These intermediate states show mixed metabolic profiles. For example, they might use both glycolysis (typical of M1) and oxidative phosphorylation (typical of M2) simultaneously, or switch between these metabolic pathways depending on available nutrients and tissue demands.

Tissue-specific macrophage populations and their plasticity

The plasticity of macrophages varies across different tissues, reflecting the functional demands of each anatomical location.21 Tissue-resident macrophages develop specialized characteristics while maintaining their plasticity.

Specialized macrophage populations

Different tissues harbor distinct macrophage populations.12 The existence of distinct tissue-resident macrophages with specialized functions is a clear example of macrophage plasticity in action. It shows how a single cell type can adapt its identity and behavior in response to its location and the signals it receives.

- Alveolar macrophages (lungs): Involved in particle clearance and surfactant metabolism

- Kupffer cells (liver): Specialize in detoxification and metabolic regulation

- Microglia (brain): Maintain neural homeostasis and respond to neuroinflammation

- Osteoclasts (bone): Control bone remodeling and calcium homeostasis

- Tumor-associated macrophages: Adapt to tumor microenvironments

Environmental influences on plasticity

Macrophage plasticity is profoundly shaped by the environment in which these cells reside through various mechanisms21–23:

- Hypoxia: In low-oxygen environments (like inside tumors or inflamed tissues), macrophages often shift toward an M2-like phenotype, which is anti-inflammatory and supports tissue remodeling or tumor growth.

- Mechanical forces: Tissues under physical stress or strain (like in fibrosis, tumors, or muscle injury) can mechanically influence macrophage activation. For instance, stiffness of the surrounding tissue can push macrophages toward a pro- or anti-inflammatory state.

- Cell-cell interactions: Direct contact with nearby cells (like fibroblasts, epithelial cells, or tumor cells) can change how macrophages behave by providing surface signals or feedback.

- Metabolic factors: The availability of nutrients like glucose, lipids, or amino acids in the local tissue environment can influence whether macrophages adopt a pro-inflammatory (M1) or repair-oriented (M2) state.

Macrophage plasticity in disease

Macrophage plasticity plays a pivotal role in disease development and progression. Different macrophage populations can either promote or prevent disease, depending on their activation state and the tissue context.21

Figure 3: Disease context shapes macrophage function. Macrophage plasticity plays opposing roles in different diseases. In cancer, tumor progression promotes M2-like phenotypes that support growth and metastasis. In chronic inflammatory diseases, persistent M1 activation drives tissue damage. Therapeutic approaches aim to restore beneficial activation patterns.

Chronic inflammation and autoimmune diseases

Macrophage plasticity and function become dysregulated in several chronic inflammatory conditions:

- Rheumatoid arthritis: Persistent M1 activation drives joint destruction24

- Atherosclerosis: Macrophage infiltration promotes plaque formation25

- Inflammatory bowel disease: Imbalanced M1/M2 responses perpetuate inflammation26

In these pathological contexts, excessive production of pro-inflammatory mediators by M1-polarized macrophages contributes to tissue injury. As a result, therapeutic approaches often aim to modulate macrophage activity, shifting polarization toward M2 phenotypes or dampening prolonged inflammatory responses.27

Cancer and tumor progression

Macrophages play an important role in cancer development and progression. Tumor cells reprogram the surrounding macrophages to support their growth, and the effects of macrophages on tumor cells depend on the stage of cancer28–30:

- Early cancer: M1 macrophages may contribute to anti-tumor immunity by eliminating cancer cells

- Established tumors: M2-like macrophages promote tumor progression

- Metastasis: Polarized macrophages facilitate cancer cell spread

- Therapy resistance: Tumor-associated macrophages can mediate resistance to cancer therapies

The tumor microenvironment promotes a shift from M1 to M2 phenotypes, creating a niche that enhances tumor growth.30 Therefore, scientists are developing new immunotherapy approaches to macrophage reprogramming in the tumor microenvironment.

Wound healing and tissue repair

Unlike the dysregulated macrophage responses observed in chronic inflammatory diseases and cancer, the plasticity of macrophages plays an essential role in wound healing and tissue repair15:

- Initial response: M1 macrophages clear debris and fight infection

- Transition phase: Gradual shift toward M2 phenotypes

- Resolution: M2 macrophages promote tissue regeneration

- Homeostasis: Return to baseline surveillance functions

Disruption of macrophage plasticity can lead to chronic wounds or excessive scarring, highlighting the importance of a balanced inflammatory response.

Challenges in macrophage nomenclature

The complexity of macrophage plasticity has created challenges for researchers attempting to classify and communicate the different phenotypes of macrophages. The proliferation of different naming systems has led to confusion in the scientific literature.

The "Tower of Babel" problem

In a 2014 article on macrophage nomenclature, Dr. Peter J. Murray of St. Jude Children's Research Hospital compared the current state of macrophage nomenclature to the biblical Tower of Babel, where confusion of tongues prevented project completion.31 Without standardized terminology, researchers face challenges in comparing results across laboratories, reproducing experimental findings, and translating their research findings to clinical applications.

Potential solutions for standardization

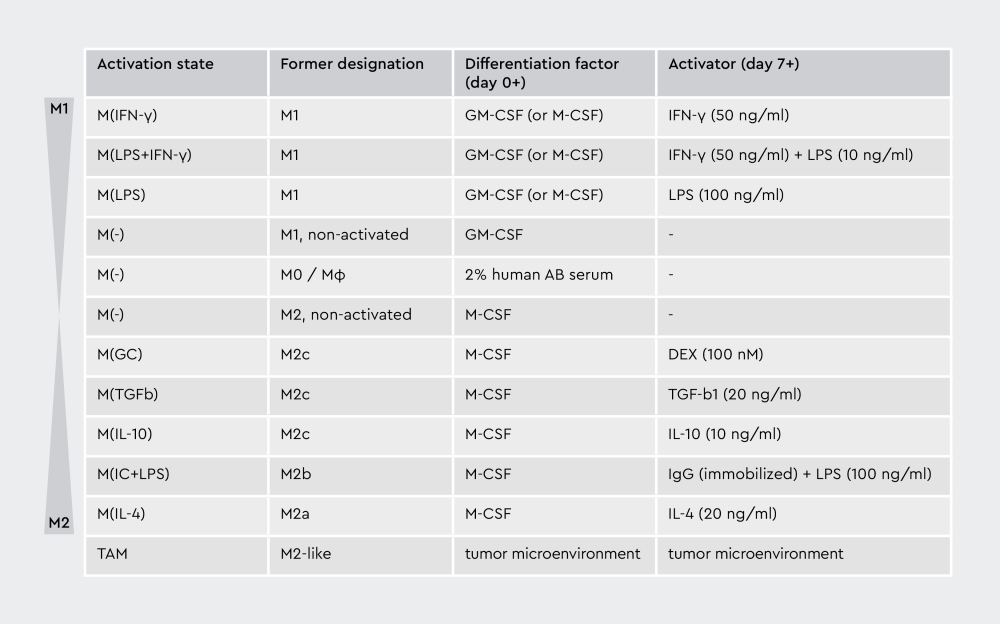

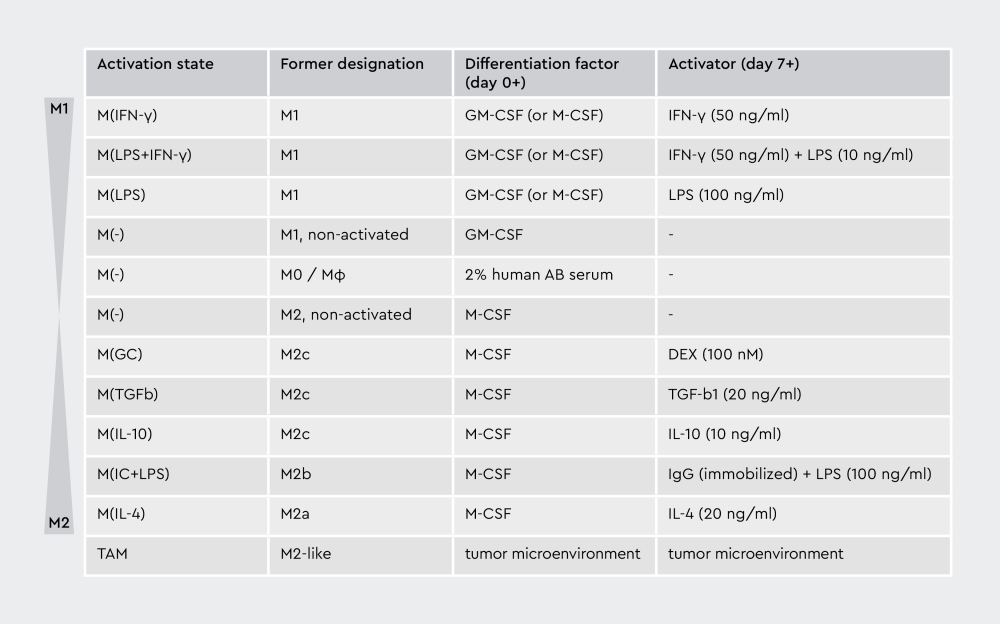

To address these challenges, researchers have proposed several standardization approaches. For example, Murray and colleagues recommended the use of stimulus-based nomenclature, such as M(IL-4), M(IFN-γ), and M(LPS); the development of reproducible experimental standards; the implementation of minimal reporting requirements; and the avoidance of overly complex classification schemes.31

At PromoCell, we adhere to the nomenclature of Dr. Murray, as it precisely defines how macrophages are differentiated in vitro and which cytokines are used for their polarization and subsequent activation. “This allows scientists to reproduce and standardize the experimental processes,” says Wieland. “There is a noticeable increase in reviewers and scientists who have adopted Murray’s nomenclature in their works since 2014. This way, they can better present their results.”

This approach has gained further support from other researchers in the field, with a 2023 review reinforcing the continuum view of macrophage activation and emphasizing the importance of Murray’s precise nomenclature framework for advancing the field.32

Experimental approaches to study macrophage plasticity

Studying macrophage plasticity requires experimental approaches that can capture the dynamic nature of these cells. Both in vitro and in vivo methods have been developed to study macrophage plasticity.

In vitro systems

In vitro models remain fundamental tools for dissecting macrophage plasticity and commonly employed approaches include33–35:

- Primary macrophages: Derived from blood monocytes or bone marrow

- Standardized culture conditions: Defined media and activation protocols

- Polarization stimuli: Specific cytokines to induce M1 or M2 states

- Functional assays: Tests of phagocytosis, cytokine production, and metabolism

In vitro studies of macrophage plasticity enable controlled experimental conditions, reproducible results across laboratories, cost-effective screening approaches, and detailed mechanistic investigations.

In vivo models

Animal models provide critical insights into macrophage plasticity in physiological contexts35–37:

- Disease-specific models: Cancer, inflammation, and infection studies

- Genetic approaches: Conditional knockouts and reporter systems

- Cell tracking: Following macrophage behavior over time

- Advanced tissue analysis: Single-cell sequencing and spatial profiling

Emerging technologies

New technologies have been developed to study the plasticity of macrophages:

- Single-cell RNA sequencing: Reveals heterogeneity within populations38

- Spatial transcriptomics: Maps gene expression in tissue context38

- Live imaging: Tracks dynamic changes in real-time39,40

- Computational modeling: Predicts plasticity responses41

Therapeutic implications and future directions

The growing understanding of macrophage plasticity is opening new opportunities for the treatment of several diseases by targeting the mechanisms that control macrophage polarization.

Several strategies target macrophage plasticity for therapeutic benefit42–45:

- Repolarization therapy: Converting M2 to M1 phenotypes in cancer

- Blocking recruitment: Preventing macrophage infiltration into tumors

- Enhancing resolution: Promoting M2 responses to resolve inflammation

- Metabolic targeting: Altering macrophage metabolism to change function

Challenges

The development of macrophage-targeted therapies faces several obstacles21,46:

- Selectivity: Avoiding effects on beneficial macrophage functions

- Targeted delivery: Getting drugs to the right tissue locations

- Timing: Coordinating interventions with disease progression

- Heterogeneity: Accounting for diverse macrophage populations

The role of standardization in clinical translation

To successfully translate macrophage plasticity research into clinical applications, researchers need robust standardization of experimental approaches and terminology.

Several organizations are working toward standardization:

- International consortia: Coordinating research efforts globally

- Professional societies: Developing best practice guidelines

- Regulatory agencies: Establishing requirements for therapeutic development

- Commercial partners: Providing standardized reagents and protocols

Adopting common standards offers multiple advantages, including easier comparison and combination of studies, smoother transition from research to clinical applications, and reduced time and resources spent on conflicting results.

Ready to advance your macrophage research?

Explore our comprehensive portfolio of primary human macrophages, optimized culture media, and polarization reagents. Our standardized systems support reproducible research and accelerate your path to discovery. Contact our technical team to discuss your research needs and access protocols based on established nomenclature standards.

References

Expand

- Locati M, Curtale G, Mantovani A. Diversity, mechanisms and significance of macrophage plasticity. Annu Rev Pathol. 2020;15:123-147. doi:10.1146/annurev-pathmechdis-012418-012718

- Mantovani A, Sica A, Sozzani S, Allavena P, Vecchi A, Locati M. The chemokine system in diverse forms of macrophage activation and polarization. Trends Immunol. 2004;25(12):677-686. doi:10.1016/j.it.2004.09.015

- Genard G, Lucas S, Michiels C. Reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages with anticancer therapies: radiotherapy versus chemo- and immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2017;8:828. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2017.00828

- Interleukin 4 potently enhances murine macrophage mannose receptor activity: a marker of alternative immunologic macrophage activation. J Exp Med. 1992;176(1):287-292. doi:10.1084/jem.176.1.287

- Mills CD, Kincaid K, Alt JM, Heilman MJ, Hill AM. M-1/M-2 macrophages and the Th1/Th2 paradigm1. The Journal of Immunology. 2000;164(12):6166-6173. doi:10.4049/jimmunol.164.12.6166

- Chen Y, Zhang X. Pivotal regulators of tissue homeostasis and cancer: macrophages. Experimental Hematology & Oncology. 2017;6(1):23. doi:10.1186/s40164-017-0083-4

- Han IH, Song HO, Ryu JS. IL-6 produced by prostate epithelial cells stimulated with Trichomonas vaginalis promotes proliferation of prostate cancer cells by inducing M2 polarization of THP-1-derived macrophages. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2020;14(3):e0008126. doi:10.1371/journal.pntd.0008126

- Huang J, Fu X, Chen X, Li Z, Huang Y, Liang C. Promising therapeutic targets for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:686155. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2021.686155

- Wynn TA, Vannella KM. Macrophages in tissue repair, regeneration, and fibrosis. Immunity. 2016;44(3):450-462. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2016.02.015

- Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889-896. doi:10.1038/ni.1937

- Xue JD, Gao J, Tang AF, Feng C. Shaping the immune landscape: Multidimensional environmental stimuli refine macrophage polarization and foster revolutionary approaches in tissue regeneration. Heliyon. 2024;10(17):e37192. doi:10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e37192

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11(11):723-737. doi:10.1038/nri3073

- Murray PJ, Wynn TA. Obstacles and opportunities for understanding macrophage polarization. Journal of Leukocyte Biology. 2011;89(4):557-563. doi:10.1189/jlb.0710409

- Menzies FM, Henriquez FL, Alexander J, Roberts CW. Sequential expression of macrophage anti-microbial/inflammatory and wound healing markers following innate, alternative and classical activation. Clinical and Experimental Immunology. 2010;160(3):369-379. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2249.2009.04086.x

- Yan L, Wang J, Cai X, et al. Macrophage plasticity: signaling pathways, tissue repair, and regeneration. MedComm (2020). 2024;5(8):e658. doi:10.1002/mco2.658

- Wang N, Liang H, Zen K. Molecular mechanisms that influence the macrophage M1–M2 polarization balance. Front Immunol. 2014;5:614. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2014.00614

- Liu Y, Xu R, Gu H, et al. Metabolic reprogramming in macrophage responses. Biomarker Research. 2021;9(1):1. doi:10.1186/s40364-020-00251-y

- Wculek SK, Dunphy G, Heras-Murillo I, Mastrangelo A, Sancho D. Metabolism of tissue macrophages in homeostasis and pathology. Cell Mol Immunol. 2022;19(3):384-408. doi:10.1038/s41423-021-00791-9

- Viola A, Munari F, Sánchez-Rodríguez R, Scolaro T, Castegna A. The metabolic signature of macrophage responses. Front Immunol. 2019;10:1462. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2019.01462

- Wang L, Wang D, Zhang T, Ma Y, Tong X, Fan H. The role of immunometabolism in macrophage polarization and its impact on acute lung injury/acute respiratory distress syndrome. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1117548. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1117548

- Guan F, Wang R, Yi Z, et al. Tissue macrophages: origin, heterogenity, biological functions, diseases and therapeutic targets. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2025;10(1):93. doi:10.1038/s41392-025-02124-y

- Bai R, Li Y, Jian L, Yang Y, Zhao L, Wei M. The hypoxia-driven crosstalk between tumor and tumor-associated macrophages: mechanisms and clinical treatment strategies. Mol Cancer. 2022;21:177. doi:10.1186/s12943-022-01645-2

- Wilson HM. Modulation of macrophages by biophysical cues in health and beyond. Discovery Immunology. 2023;2(1):kyad013. doi:10.1093/discim/kyad013

- Zheng Y, Wei K, Jiang P, et al. Macrophage polarization in rheumatoid arthritis: signaling pathways, metabolic reprogramming, and crosstalk with synovial fibroblasts. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1394108. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1394108

- Theofilis P, Oikonomou E, Tsioufis K, Tousoulis D. The role of macrophages in atherosclerosis: pathophysiologic mechanisms and treatment considerations. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2023;24(11):9568. doi:10.3390/ijms24119568

- Zhang K, Guo J, Yan W, Xu L. Macrophage polarization in inflammatory bowel disease. Cell Commun Signal. 2023;21:367. doi:10.1186/s12964-023-01386-9

- Peng Y, Zhou M, Yang H, et al. Regulatory mechanism of M1/M2 macrophage polarization in the development of autoimmune diseases. Mediators Inflamm. 2023;2023:8821610. doi:10.1155/2023/8821610

- Joshi S, Singh AR, Zulcic M, et al. Rac2 controls tumor growth, metastasis and M1-M2 macrophage differentiation in vivo. PLoS One. 2014;9(4):e95893. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0095893

- Basak U, Sarkar T, Mukherjee S, et al. Tumor-associated macrophages: an effective player of the tumor microenvironment. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1295257. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2023.1295257

- Zhang W, Wang M, Ji C, Liu X, Gu B, Dong T. Macrophage polarization in the tumor microenvironment: emerging roles and therapeutic potentials. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. 2024;177:116930. doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2024.116930

- Murray PJ, Allen JE, Biswas SK, et al. Macrophage activation and polarization: nomenclature and experimental guidelines. Immunity. 2014;41(1):14-20. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2014.06.008

- Katkar G, Ghosh P. Macrophage states: there’s a method in the madness. Trends in Immunology. 2023;44(12):954-964. doi:10.1016/j.it.2023.10.006

- Hu G, Su Y, Kang BH, et al. High-throughput phenotypic screen and transcriptional analysis identify new compounds and targets for macrophage reprogramming. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):773. doi:10.1038/s41467-021-21066-x

- Parisi L, Bianchi MG, Ghezzi B, et al. Preparation of human primary macrophages to study the polarization from monocyte-derived macrophages to pro- or anti-inflammatory macrophages at biomaterial interface in vitro. Journal of Dental Sciences. 2023;18(4):1630-1637. doi:10.1016/j.jds.2023.01.020

- Herb M, Schatz V, Hadrian K, et al. Macrophage variants in laboratory research: most are well done, but some are RAW. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1457323. doi:10.3389/fcimb.2024.1457323

- Lee SE, Rudd BD, Smith NL. Fate-mapping mice: new tools and technology for immune discovery. Trends Immunol. 2022;43(3):195-209. doi:10.1016/j.it.2022.01.004

- Barclay KM, Abduljawad N, Cheng Z, et al. An inducible genetic tool to track and manipulate specific microglial states reveals their plasticity and roles in remyelination. Immunity. 2024;57(6):1394-1412.e8. doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2024.05.005

- De Zuani M, Xue H, Park JS, et al. Single-cell and spatial transcriptomics analysis of non-small cell lung cancer. Nat Commun. 2024;15(1):4388. doi:10.1038/s41467-024-48700-8

- Li Y, Liu TM. Discovering macrophage functions using in vivo optical imaging techniques. Front Immunol. 2018;9:502. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2018.00502

- Yang BQ, Chan MM, Heo GS, et al. Molecular imaging of macrophage composition and dynamics in MASLD. JHEP Rep. 2024;6(12):101220. doi:10.1016/j.jhepr.2024.101220

- Zhao C, Medeiros TX, Sové RJ, Annex BH, Popel AS. A data-driven computational model enables integrative and mechanistic characterization of dynamic macrophage polarization. iScience. 2021;24(2):102112. doi:10.1016/j.isci.2021.102112

- Shi X, Shiao SL. The role of macrophage phenotype in regulating the response to radiation therapy. Transl Res. 2018;191:64-80. doi:10.1016/j.trsl.2017.11.002

- Duan Z, Luo Y. Targeting macrophages in cancer immunotherapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):1-21. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00506-6

- Kashfi K, Kannikal J, Nath N. Macrophage reprogramming and cancer therapeutics: Role of iNOS-derived NO. Cells. 2021;10(11):3194. doi:10.3390/cells10113194

- Ghamangiz S, Jafari A, Maleki-Kakelar H, Azimi H, Mazloomi E. Reprogram to heal: Macrophage phenotypes as living therapeutics. Life Sciences. 2025;371:123601. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2025.123601

- Poltavets AS, Vishnyakova PA, Elchaninov AV, Sukhikh GT, Fatkhudinov TKh. Macrophage modification strategies for efficient cell therapy. Cells. 2020;9(6):1535. doi:10.3390/cells9061535

Related resources