3D Cell Culture

Find suitable products, scientific resources or answers to your questions within our technical library FAQ.

Checkout using your account

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Checkout as a new customer

Creating an account has many benefits:

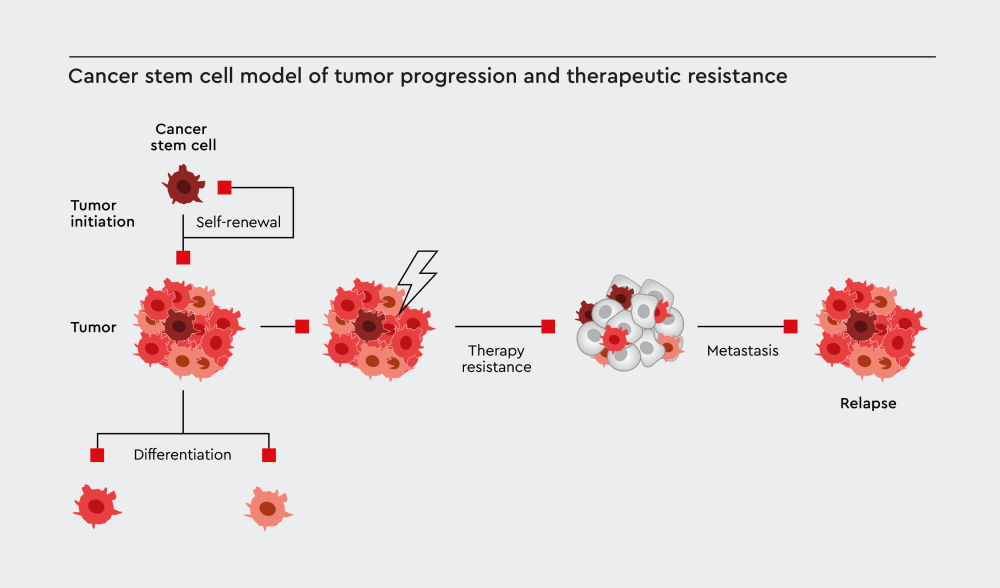

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), also known as cancer stem-like cells, represent a small population of cells within the tumor. Although rare, CSCs are promising therapeutic targets as they can rebuild entire tumors, promote resistance to cancer treatments, and drive cancer progression. Therefore, understanding the biology of CSCs is vital for developing more effective cancer therapies and improving treatment outcomes.

Cancer stem cells are rare, immortal cells within tumors that display the hallmark characteristics of stemness.1 Stemness refers to the ability of cells to self-renew, give rise to differentiated cells, and interact with their environment to maintain a balance between quiescence, proliferation, and regeneration.1,2 CSCs can self-renew through cell division while simultaneously generating the different cell types that constitute a tumor.3

Key properties of cancer stem cells:4,5

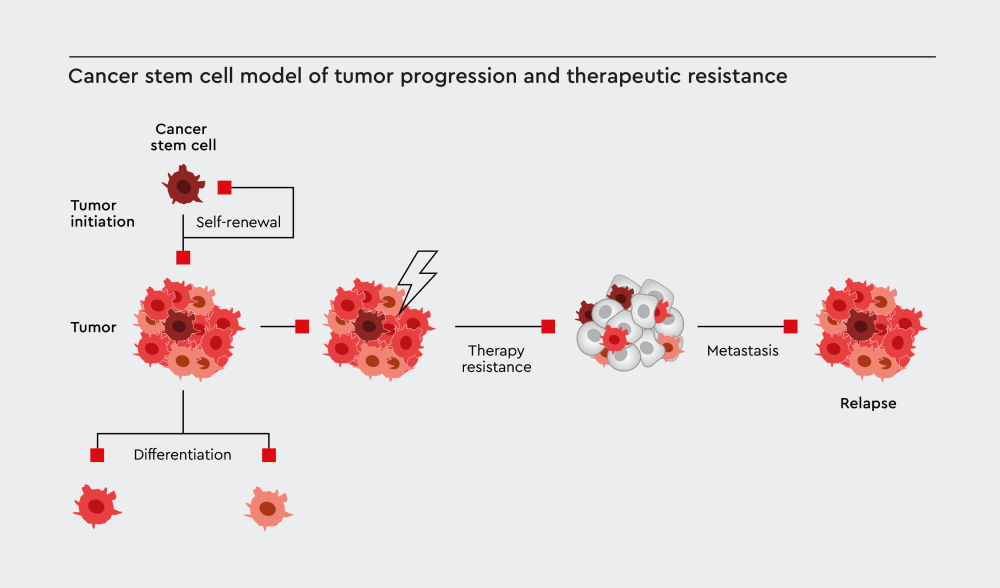

Figure 1: Cancer stem cells drive tumor initiation through self-renewal, maintain tumors through differentiation into diverse cancer cell populations, contribute to therapy resistance, and ultimately lead to metastasis and disease relapse.

Since their discovery, researchers have identified CSCs in various tumor types, making them attractive cell targets for cancer treatments.4,5 The discovery of CSCs has changed our understanding of tumor biology and opened new avenues for therapeutic intervention.

The characteristics of cancer cells can vary immensely. Solid tumors contain heterogeneous populations of cancer cells with different levels of malignant potential. This diversity plays an important role in cancer progression and treatment resistance.6,7

Cancer stem cells can reproduce themselves indefinitely, sustain long-term cancer growth, initiate new tumors, resist conventional therapies, and drive metastasis and recurrence. In contrast, regular cancer cells have limited self-renewal capacity, are more susceptible to cancer treatments, cannot maintain long-term tumor growth, and have limited ability to start new tumors.8

These differences have implications for cancer therapy. Traditional treatments like chemotherapy and radiation may shrink tumors by killing the bulk of cancer cells, but if CSCs survive, the tumor can regenerate. This explains why some cancers return after initially successful treatment.4

According to the cancer stem cell hypothesis, tumors are organized hierarchically, just like normal tissues. CSCs are at the apex of this hierarchy, giving rise to all other cell types in the tumor through multiple rounds of cell division and differentiation.9,10

This model suggests that only a small subset of cancer cells, those with stem-like properties, can initiate and maintain tumors. This hypothesis also implies that tumor growth relies on CSCs, and that eliminating CSCs could prevent tumor recurrence.11

Current scientific consensus supports this hypothesis while acknowledging that CSC biology is more complex than initially thought. Research has shown that CSCs exist in different states and can transition between stem-like and differentiated phenotypes depending on their environment.12,13

Although CSC cultures are an important cancer model that can help researchers better understand tumors, isolating and culturing CSCs in the laboratory can be challenging. One of the greatest challenges in CSC research is isolating and purifying large numbers of homogeneous CSC populations.14,15

Key challenges:

Without primary model systems, researchers must rely on indirect readouts from alternative models and functional assays. This limitation slows progress in understanding CSC biology and developing targeted therapies.

CSCs are found in small numbers in tumors, making their identification and isolation very challenging. Researchers use various approaches to characterize CSCs16,17:

Although several CSC markers have been proposed, no single marker can identify CSCs across all cancer types. The markers discovered so far lack specificity and are often expressed on other cells of the tumor or on healthy cells, albeit at different levels.18 Commonly used CSC markers include cell surface glycoprotein CD44, membrane glycoprotein CD133, aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) enzyme activity, cell adhesion molecule CD24, and epithelial cell adhesion molecule (EpCAM).19,20

Learn about our Primary Cancer Culture System (PCCS), an innovative solution that enables marker-free CSC isolation and long-term culture:

LGR5 is frequently cited as a CSC marker, but this designation is misleading. LGR5 is a common marker for various adult tissue stem cells, not specifically cancer stem cells.21,22

Researchers can identify CSCs using markers that maintain stem cell functions:

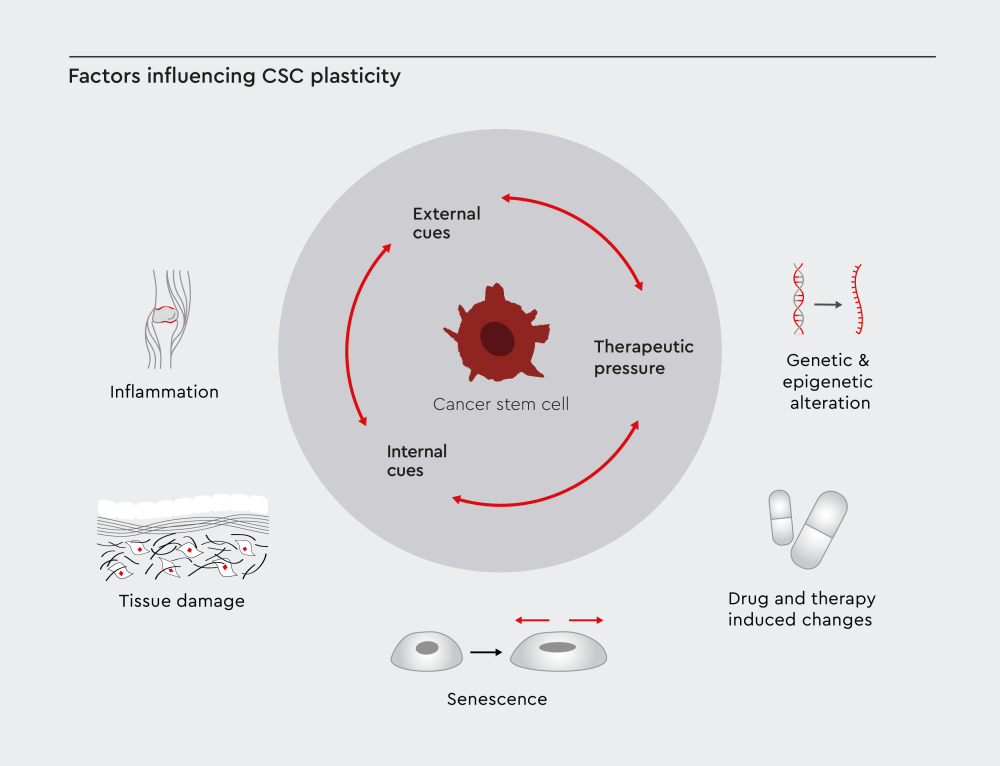

Recent studies have shown that the phenotypes of CSCs are not fixed, and that CSCs can exist in different states. The concept of CSC plasticity describes the ability of CSCs to switch between stem-like and differentiated states based on signals from their environment.13,25

Factors influencing CSC plasticity include:

Figure 2: CSC plasticity is shaped by three main factors: external cues like inflammation, tissue damage, and senescence in the tumor microenvironment; internal cues such as genetic and epigenetic changes; and therapeutic pressure caused by treatment-induced effects.

The concept of CSC plasticity supports the idea that CSCs represent a transient cell state rather than a stable cell population. Non-stem cancer cells can acquire stem-like properties under certain conditions, and CSCs can lose stem-like characteristics and become more differentiated.25,26

Solid cancers demonstrate hierarchical organization with CSCs at the top of the cellular hierarchy. CSCs were first identified in breast cancer and melanoma. Since then, researchers have found evidence of CSCs in various solid tumor types, including colon cancer, lung cancer, pancreatic cancer, prostate cancer, ovarian cancer, and glioblastoma.4,27

CSCs play an important role in cancer progression in patients with solid tumors, making them promising targets for therapeutic intervention. The self-renewal capacity and differentiation potential of CSCs contribute to their ability to promote tumor growth, repopulation after therapy, and metastasis to distant sites.4

Hematological malignancies also contain CSCs, which are often called leukemia stem cells (LSCs). These cells possess self-renewal capabilities and are responsible for long-term disease maintenance.28 Researchers believe that patient outcomes in blood cancers are closely linked to the properties of LSCs. These cells have the ability to self-renew indefinitely, show resistance to conventional therapies, interact with bone marrow niches, and have the capacity to reinitiate disease.28,29

Achieving a cure in patients with blood cancer may depend on completely eradicating these persistent cells.

Studies suggest that cancer relapse occurs because quiescent CSCs evade current therapeutic regimens through protective mechanisms mediated by their stem cell properties.3

Mechanisms of CSC drug resistance include:

ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters have been identified as important mediators of drug resistance in CSCs. These membrane proteins act as channels that pump drugs out of cells, reducing the intracellular concentrations of anticancer drugs and limiting their therapeutic efficacy.30 ABC transporters that have been associated with chemoresistance include ABCB1 (MDR1/P-glycoprotein), ABCC1 (MRP1), and ABCG2 (BCRP).31

CSCs interact with their surrounding environment, known as the CSC niche. This microenvironment provides signals that maintain the properties of CSCs and protect them from the effects of cancer treatments.32

Components of the CSC niche include:

The interaction between CSCs and their niche influences treatment resistance and metastasis.32

Several signaling pathways regulate CSC behavior and maintain their stem-like properties and their ability to evade the effects of anticancer drugs.33

CSC signaling pathways include:

Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) is a cellular process during which cells lose their epithelial characteristics and acquire mesenchymal properties. EMT in CSCs increases cell motility and invasiveness, enhances stem-like properties, promotes therapy resistance, and facilitates metastasis.34

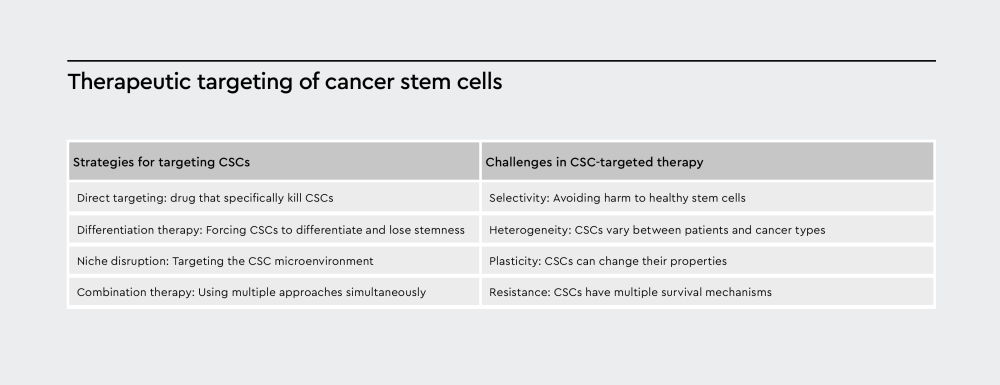

Eliminating CSCs could lead to long-lasting remission and improve long-term treatment outcomes in patients with cancer.35 However, developing CSC-targeted therapies presents several challenges.

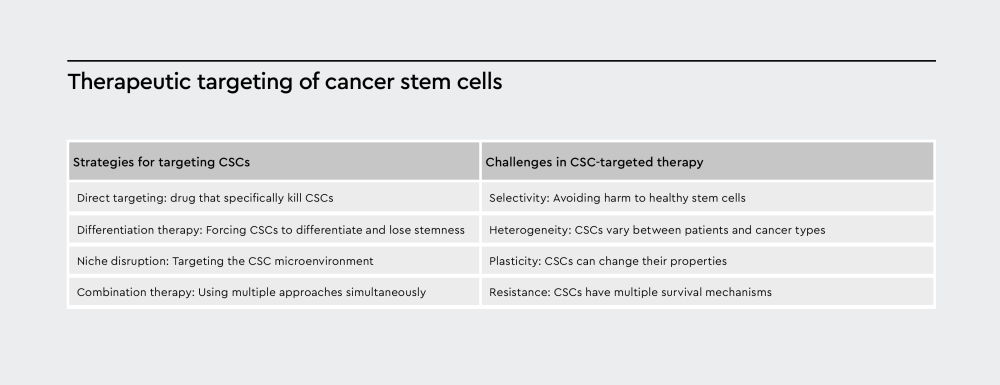

Figure 3: The scheme summarizes strategies for targeting CSCs and challenges in CSC-targeted therapies.

Gaining a better understanding of CSCs can affect how we approach cancer treatment. Traditional cancer therapies that focus on tumor shrinkage may be insufficient if CSCs survive and drive recurrence. Therefore, combination approaches under development aim to target both CSCs and bulk tumor cells.4 In addition, tracking CSCs during treatment can be used to monitor treatment response, while targeting CSCs can help prevent metastasis.4

Immunotherapy is a promising strategy for targeting CSCs, as the immune system can potentially recognize and eliminate CSCs while sparing normal cells.36 Investigational immune-based CSC strategies include engineered CAR-T cells targeting CSC markers, vaccines stimulating immune responses against CSCs, and the adoptive transfer of immune cells that target CSCs.36

Minimal residual disease (MRD) refers to the small number of cancer cells that remain after treatment. These cells are often enriched for CSCs and may be responsible for cancer recurrence.37 CSCs may constitute a significant portion of MRD, but traditional detection methods may miss CSCs. Recent studies suggest that CSC-specific markers could improve MRD detection, and that targeting MRD CSCs could prevent recurrence.38,39

References

Have a look at other Research Areas

PromoCell uses HubSpot to provide LiveChat support. This feature is currently blocked due to your cookie preferences.

Accept cookies to enable LiveChat