Not all cancer cells within a single tumor have the same characteristics. The tumor microenvironment contains various subsets of cancer cells. The characteristics of each subgroup can influence tumor growth, metastasis, and treatment resistance. Read on to learn how these cellular differences affect cancer progression and treatment outcomes.

What is intratumoral heterogeneity?

Intratumoral heterogeneity refers to the presence of genetically and phenotypically distinct cell subpopulations within a single tumor.1–3 Tumors are not uniform masses of identical cells; rather, they contain multiple subsets of cancer cells that differ in their molecular profiles, malignancy, and responses to therapy. These subsets are not randomly distributed but exist in specific spatial niches throughout the tumor, making spatial biology an increasingly important area of research.

Mechanisms that contribute to intratumoral heterogeneity include3,4

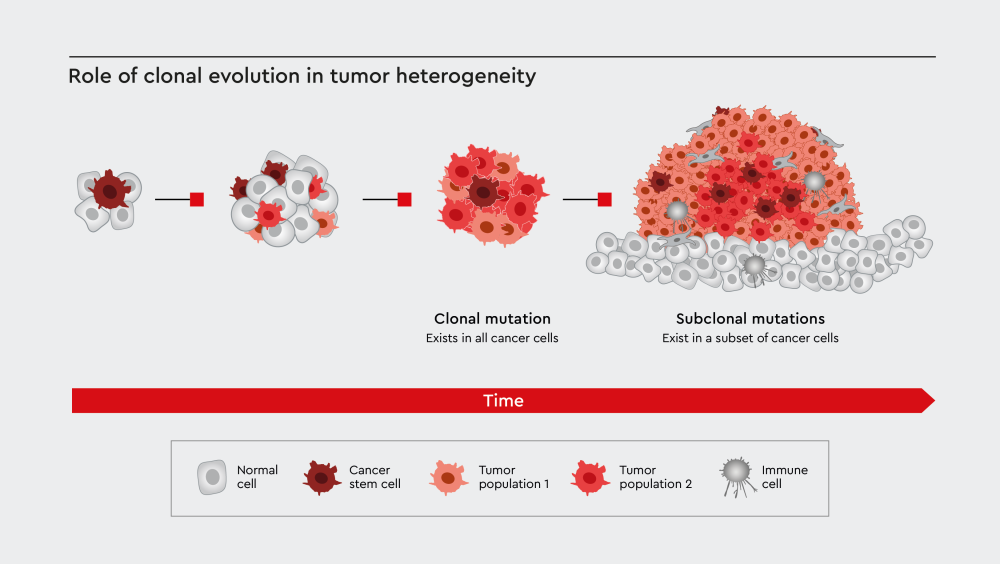

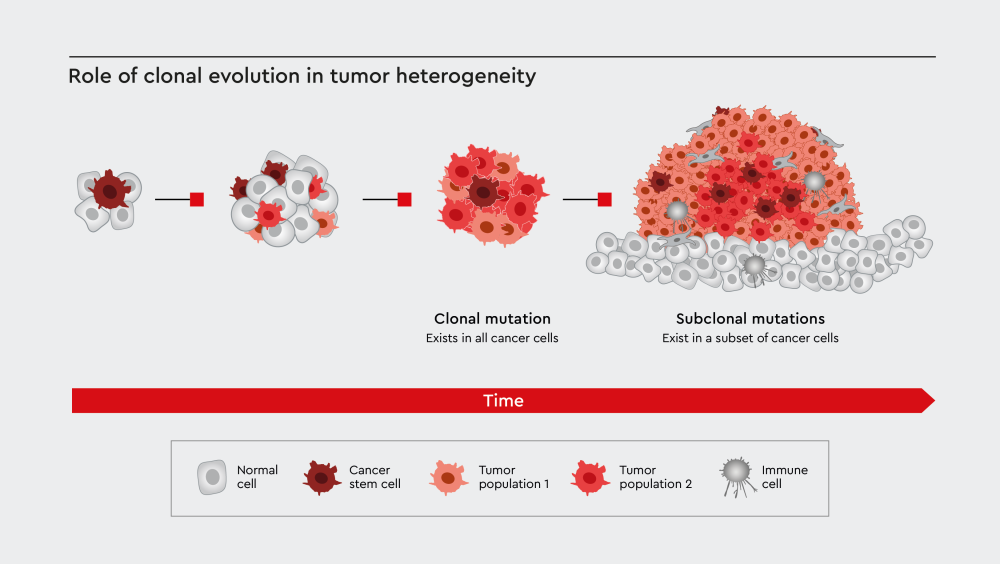

- Clonal evolution: Cancer cells can accumulate mutations over time, resulting in subpopulations that are genetically distinct from one another.

- Epigenetic alterations: Modifications in gene expression of cancer cell subpopulations without changes in DNA sequence.

- Microenvironmental signals: Local conditions that push cancer cells toward different states.

- Cancer cell plasticity: The ability of cells to switch between different phenotypic states.

Different cancer cell subsets within the same tumor can exhibit varying sensitivities to treatment, with some populations driving resistance and recurrence.5 This complexity explains why many cancer therapies that initially show promise ultimately fail as resistant cell populations emerge and proliferate.

Figure 1: Clonal evolution contributes to tumor heterogeneity through the generation of cancer cell subpopulations with subclonal mutations. Adopted from El-Sayes et al.6

Cancer cell subsets

Tumors contain several subsets of tumor cells, each of which plays an important role in cancer progression. In addition to the different cancer cell subsets, the tumor microenvironment also includes other cell types such as cancer-associated fibroblasts (CAFs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs). These cells contribute to tumor heterogeneity.

What are cancer stem cells?

Cancer stem cells (CSCs), also known as cancer stem-like cells, are a subset of cancer cells that are able to self-renew and proliferate indefinitely.7 CSCs can give rise to various cell types found within tumors and play an important role in cancer progression, metastasis, and recurrence.7–9

Characteristics of cancer stem cells include10

- Self-renewal capacity: CSCs can divide to produce more stem cells.

- Differentiation potential: They can differentiate into various cell types within tumors.

- Treatment resistance: CSCs often survive chemotherapy and radiation.

- Metastatic capability: They can initiate tumor formation at distant sites.

Researchers have identified CSCs in various cancer types, including breast cancer, pancreatic cancer, and brain tumors.7 CSCs express high levels of stem cell biomarkers and can repair DNA damage, contributing to their ability to survive cytotoxic therapies and promote cancer progression.7,11

What are drug-tolerant persister cells?

Drug-tolerant persister cells (DTPs) are cancer cells that survive anticancer treatments despite being genetically susceptible to those therapies. DTPs survive through non-genetic mechanisms, entering a temporary tolerant state that allows them to survive cancer treatment.12

DTPs can return to a sensitive state after treatment ends and often exist in a quiescent or slow-proliferating state. Studies have shown that DTPs alter their cellular metabolism in response to treatment to survive stress.13,14 Understanding DTPs has revealed new insights into how minimal residual disease develops and why cancer relapse occurs even after successful treatment.12

What are dormant cancer cells?

Dormant cancer cells are a subset of cancer cells that exist in a non-proliferative state for extended periods.15 They can evade detection by the immune system and treatment, remaining quiescent for months or years before starting to form new tumors. They can also avoid detection by immune cell subsets and withstand various cellular stresses.15

Dormant cancer cells show reduced metabolic activity, which helps them survive under stress. When conditions become favorable, dormant cancer cells can resume proliferation and establish new tumors.16 Dormant cancer cells are particularly relevant in understanding tumor recurrence, as they may explain why some patients experience cancer relapse years after initial treatment.16

What are circulating tumor cells?

Circulating tumor cells (CTCs) are cancer cells that detach from the primary tumor and enter the circulation. Although CTCs are essential for metastasis, only a small fraction of cells successfully establish metastatic tumors.17

The characteristics of CTCs include18

- Epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT): CTCs undergo phenotypic changes that facilitate migration.

- Survival in circulation: They must withstand the hostile environment of the bloodstream.

- Metastasis-initiating potential: Some CTCs have the ability to establish tumors at distant sites.

- Heterogeneous populations: CTCs include various cell types with different metastatic capabilities.

The study of CTCs has provided valuable insights into the mechanisms underlying metastasis and offers a method for monitoring treatment response and disease progression.17

How does tumor heterogeneity affect treatment outcomes?

Heterogeneous tumors contain subpopulations of cancer cells with varying sensitivities to cancer treatments.19 Targeted therapy using agents that target specific molecular pathways or cellular mechanisms may only eliminate one or a few subsets of cancer cells while leaving others unaffected.19 This selective pressure can lead to clonal selection, allowing treatment-resistant populations to expand and repopulate the tumor. This heterogeneity also presents challenges for adaptive cell therapies like CAR-T cell therapy, as it makes it difficult to identify unique tumor antigens that are consistently expressed across all cancer cell subsets.20

The presence of multiple cancer cell subsets within tumors necessitates the use of combination therapies that can inhibit different cellular pathways and eliminate different cell populations.19 Using different therapies in succession and adjusting therapy based on tumor evolution are additional strategies for preventing resistance. Understanding how different cancer cell subsets respond to therapy has become essential for developing more effective treatment strategies and improving patient outcomes.

Role of CSCs in cancer relapse

CSCs can survive chemotherapy and radiation therapy that eliminates the bulk of tumor cells.7,21 The ability of CSCs to survive treatment stems from their enhanced DNA repair capabilities, drug efflux mechanisms, and altered cell cycle.7 Standard cancer treatments target rapidly dividing cells, but CSCs can remain in a quiescent state to survive therapy.21 After treatment ends, surviving CSCs can proliferate and can regenerate entire tumor populations, leading to disease recurrence. CSCs can also initiate tumors at new sites and may acquire additional resistance mechanisms over time.7

Can cancer cell subsets be targeted with therapy?

Several approaches have been proposed to selectively eliminate or control different cell populations within tumors.

Targeting cancer stem cells

Strategies targeting CSCs include22

- Differentiation therapy: Forces CSCs to differentiate into non-stem cell types

- Self-renewal inhibition: Blocks pathways that maintain stemness

- Metabolic targeting: Alters metabolic pathways of CSC

- Immunotherapy: Enhances immune system recognition of CSCs

Targeting drug-tolerant persister cells

Therapeutic approaches for eliminating DTPs include the use of multiple drugs to prevent tolerance development, intermittent dosing to prevent cells from entering the persister state, and metabolic inhibitors targeting the altered metabolism of DTPs.23 Epigenetic modulators have also been developed to reverse epigenetic changes that promote tolerance.23

Dormant cells

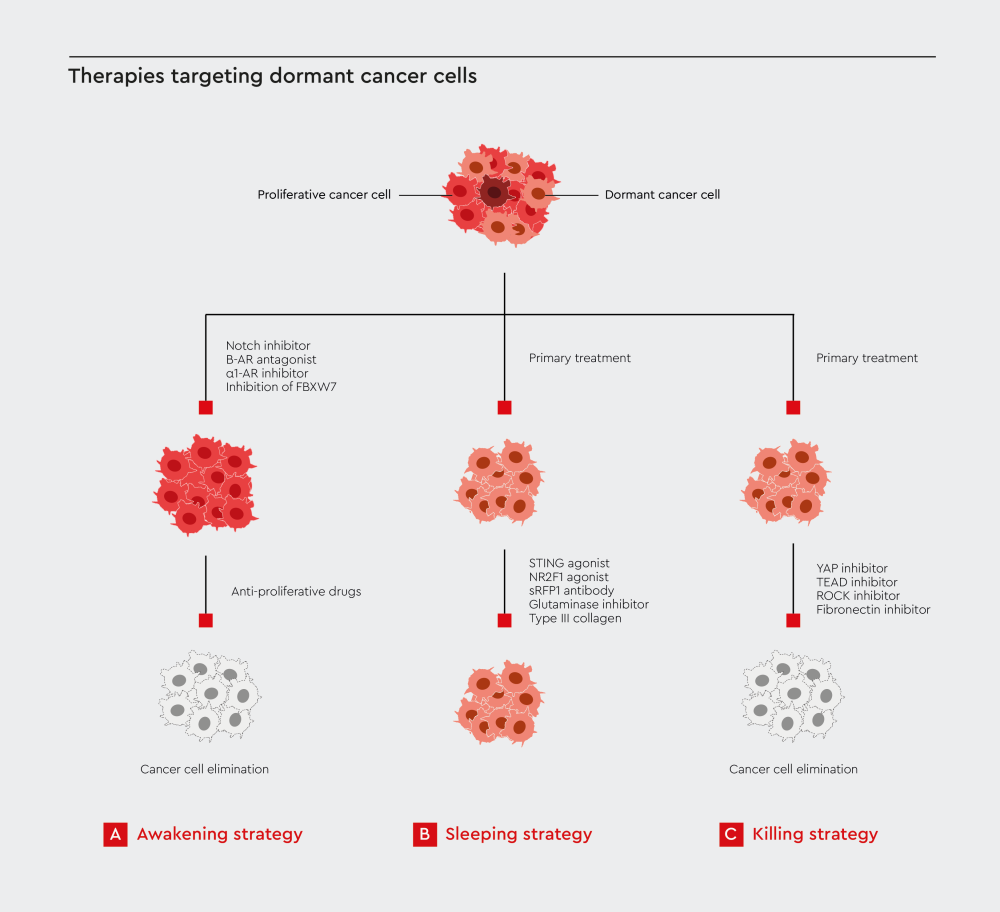

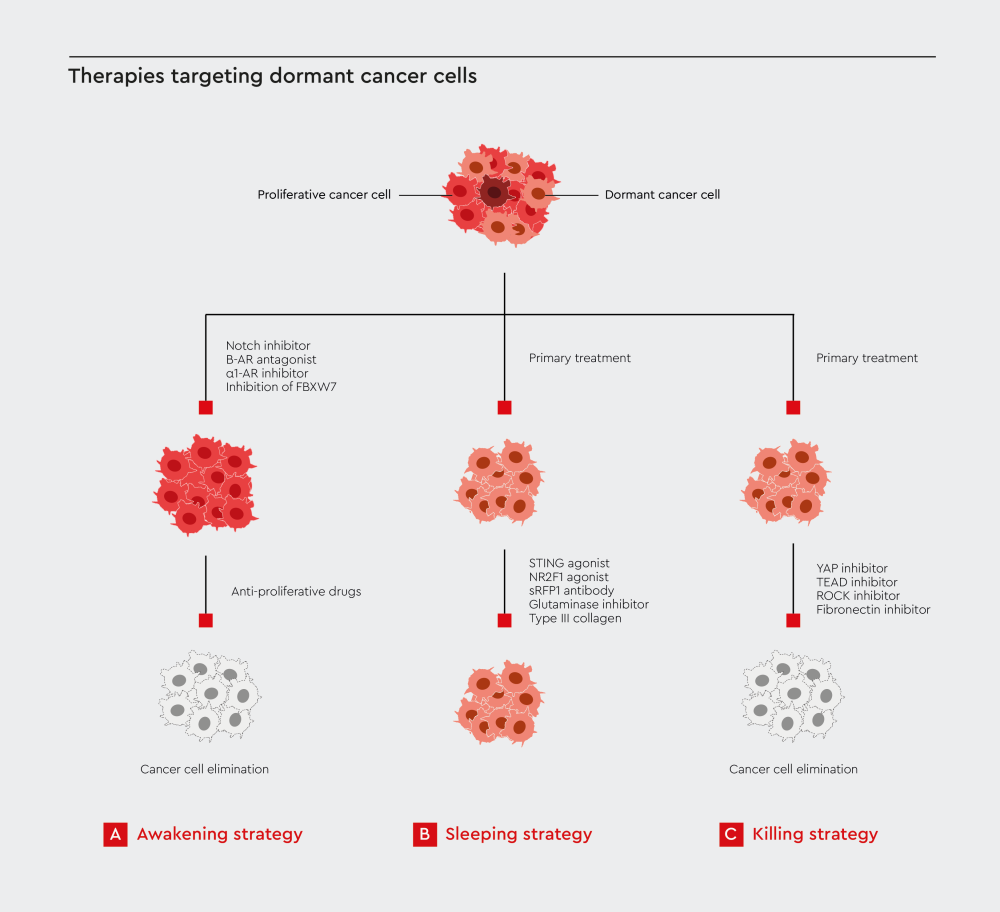

Strategies for eliminating dormant cancer cells include24

- Forced reactivation: Makes dormant cells proliferate and become therapy-sensitive

- Microenvironment modulation: Reverses conditions that support dormancy

- Immune enhancement: Improves immune system detection of dormant cells, and targeted elimination of dormant cells

Figure 2: Therapies targeting dormant cancer cells. Strategies for eliminating dormant cancer cells include forced reactivation, microenvironment modulation, and targeted cell killing. Adopted from Yang et al.24

Importance of studying cancer cell subsets

Understanding the different subsets of cancer cells within tumors has several clinical implications. As such, the ability to study these cell populations in controlled laboratory conditions is essential for the development of more effective cancer therapies. Researchers need specialized tools and culture systems that can maintain the characteristics of each cell subset while allowing for detailed analysis of their behavior, drug responses, and interactions. Research on cancer cell heterogeneity can help inform the development of more personalized treatment approaches and adoptive cell therapies that can target multiple cancer cell populations.

Our Cancer Media Toolbox

A trio of functional media enables you to study cancer cell subsets in detail. Explore our cancer research solutions and advance your understanding of tumor heterogeneity.

References

Expand

- Marusyk A, Almendro V, Polyak K. Intra-tumour heterogeneity: a looking glass for cancer? Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12(5):323-334. doi:10.1038/nrc3261

- Caiado F, Silva-Santos B, Norell H. Intra-tumour heterogeneity – going beyond genetics. The FEBS Journal. 2016;283(12):2245-2258. doi:10.1111/febs.13705

- Hinohara K, Polyak K. Intratumoral Heterogeneity: More Than Just Mutations. Trends in Cell Biology. 2019;29(7):569-579. doi:10.1016/j.tcb.2019.03.003

- Sun X, Yu Q. Intra-tumor heterogeneity of cancer cells and its implications for cancer treatment. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2015;36(10):1219-1227. doi:10.1038/aps.2015.92

- Dagogo-Jack I, Shaw AT. Tumour heterogeneity and resistance to cancer therapies. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2018;15(2):81-94. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.166

- El-Sayes N, Vito A, Mossman K. Tumor heterogeneity: a great barrier in the age of cancer immunotherapy. Cancers. 2021;13(4):806. doi:10.3390/cancers13040806

- Najafi M, Farhood B, Mortezaee K. Cancer stem cells (CSCs) in cancer progression and therapy. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234(6):8381-8395. doi:10.1002/jcp.27740

- Li Y, Wang Z, Ajani JA, Song S. Drug resistance and cancer stem cells. Cell Commun Signal. 2021;19(1):19. doi:10.1186/s12964-020-00627-5

- Richard V, Kumar TRS, Pillai RM. Transitional dynamics of cancer stem cells in invasion and metastasis. Transl Oncol. 2021;14(1):100909. doi:10.1016/j.tranon.2020.100909

- Chu X, Tian W, Ning J, et al. Cancer stem cells: advances in knowledge and implications for cancer therapy. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):170. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01851-y

- Maugeri-Saccà M, Bartucci M, De Maria R. DNA damage repair pathways in cancer stem cells. Mol Cancer Ther. 2012;11(8):1627-1636. doi:10.1158/1535-7163.mct-11-1040

- De Conti G, Dias MH, Bernards R. Fighting drug resistance through the targeting of drug-tolerant persister cells. Cancers. 2021;13(5):1118. doi:10.3390/cancers13051118

- Zhang Z, Tan Y, Huang C, Wei X. Redox signaling in drug-tolerant persister cells as an emerging therapeutic target. eBioMedicine. 2023;89. doi:10.1016/j.ebiom.2023.104483

- He J, Qiu Z, Fan J, Xie X, Sheng Q, Sui X. Drug tolerant persister cell plasticity in cancer: a revolutionary strategy for more effective anticancer therapies. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2024;9(1):209. doi:10.1038/s41392-024-01891-4

- Liu R, Zhao Y, Su S, et al. Unveiling cancer dormancy: Intrinsic mechanisms and extrinsic forces. Cancer Lett. 2024;591:216899. doi:10.1016/j.canlet.2024.216899

- Santos-de-Frutos K, Djouder N. When dormancy fuels tumour relapse. Commun Biol. 2021;4(1):747. doi:10.1038/s42003-021-02257-0

- Lin D, Shen L, Luo M, et al. Circulating tumor cells: biology and clinical significance. Sig Transduct Target Ther. 2021;6(1):404. doi:10.1038/s41392-021-00817-8

- Pantel K, Speicher MR. The biology of circulating tumor cells. Oncogene. 2016;35(10):1216-1224. doi:10.1038/onc.2015.192

- Lopez JS, Banerji U. Combine and conquer: challenges for targeted therapy combinations in early phase trials. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017;14(1):57-66. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2016.96

- Zhang B, Wu J, Jiang H, Zhou M. Strategies to overcome antigen heterogeneity in CAR-T cell therapy. Cells. 2025;14(5):320. doi:10.3390/cells14050320

- Olivares-Urbano MA, Griñán-Lisón C, Marchal JA, Núñez MI. CSC radioresistance: a therapeutic challenge to improve radiotherapy effectiveness in cancer. Cells. 2020;9(7):1651. doi:10.3390/cells9071651

- Dzobo K, Senthebane DA, Ganz C, Thomford NE, Wonkam A, Dandara C. Advances in therapeutic targeting of cancer stem cells within the tumor microenvironment: an updated review. Cells. 2020;9(8):1896. doi:10.3390/cells9081896

- Song X, Lan Y, Zheng X, et al. Targeting drug‐tolerant cells: A promising strategy for overcoming acquired drug resistance in cancer cells. MedComm (2020). 2023;4(5):e342. doi:10.1002/mco2.342

- Yang S, Seo J, Choi J, et al. Towards understanding cancer dormancy over strategic hitching up mechanisms to technologies. Mol Cancer. 2025;24(1):47. doi:10.1186/s12943-025-02250-9

Related resources